The Book That Predicted the Return of Great Power Conflict

By Jose Nino

Institute for Historical Review

May 2025

John Mearsheimer

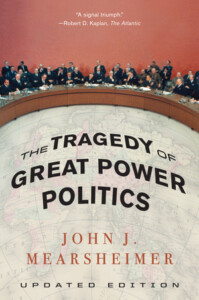

In years when so many politicians and foreign policy experts waxed poetically about their vision of a “rules-based international order” of enduring global harmony, John Mearsheimer persistently warned against the delusions and dangers of this outlook. For years he has been a leading voice for a realist foreign policy, an outlook impressively laid out in his most important work, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. First published in 2001, the author explains his theory of offensive realism, presented as part of a hard-nosed examination of international politics rooted not in sentiment or presumed idealism, but in the immutable realities of power politics.

Mearsheimer, the Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago, is perhaps best known for his controversial 2007 work The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, co-authored with Harvard international affairs professor Stephen Walt. However, it is The Tragedy of Great Power Politics that most thoroughly lays out his view of international relations.

Reading it today, one cannot help but be struck by how the events of recent decades validate the book’s central thesis. His insights have proven to be prescient. He seems to have foreseen such geopolitical ruptures as the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the increasingly adversarial rivalry of the US and China.

Offensive Realism

At the core of Mearsheimer’s outlook is the belief that great powers are not satisfied with mere survival – they invariably seek hegemony. In a world devoid of central authority (anarchy), in which no state can ever fully discern another’s intentions, rational actors are compelled to maximize their power to secure their future. He believes that great powers are condemned to perpetual competition. “The best way to ensure survival,” he observes, “is to be the most powerful state in the system.”

He builds his central thesis on five assumptions: anarchy, offensive capabilities, uncertainty of intentions, survival as the raison d’etre of statecraft, and rationality. The result is a tragic but compelling picture of international politics: even states that want to be left alone are forced into competition, lest they fall prey to more aggressive actors. It is not evil or irrationality that drives conflict, it is reality itself.

In this way, Mearsheimer’s realism stands in stark contrast to both “liberalism” and “neoconservatism.” While liberals speak of economic interdependence and international norms, and neoconservatives push regime change in the name of “democracy,” Mearsheimer contends that material power, not ideology, drives the foreign policy decision-making of government leaders. Norms break under the weight of economic reality and great power rivalry, international institutions simply reflect actual power balances, and states cooperate only when doing so serves their interests.

Mobilizable Wealth: State Power That Matters

One of the book’s most enduring contributions is his concept of “mobilizable wealth”- which refers to the share of a nation’s economy that can effectively be directed to military use. That’s not the same as a nation’s economic output or GDP. What matters is not what a country has or produces, argues Mearsheimer, it’s what resources, human and material, a state can harness militarily in times of crisis. This distinction is crucial. A nation with a large economy, especially one that is highly-financialized or consumerist, does not necessarily wield global power and influence. What’s decisive is the ability of a nation to translate its economic strength into warships, missiles, pilots, warplanes, soldiers, artillery, tanks, and so forth. Mearsheimer explains how economic size, bureaucratic efficiency, technological creativity, innovative ability, and societal cohesion are all important factors in determining how effectively a nation can transform latent power into coercive force.

The Cold War experience is a case in point. Although the Soviet Union wielded formidable military power, its overall economy was much smaller and less dynamic than that of the United States, which meant that the USSR was not able to sustain a protracted arms race against the US. More recently, China’s rise as a great power rival of the US is best understood not in ideological terms, but rather as an ascendant power that has successfully harnessed vast human and material resources to build a robust modern economy, which has enabled it to fashion a powerful military that is making it the hegemon of east Asia.

In contrast to political leaders and international affairs specialists who are ideologically reductionist in their outlook, Mearsheimer rejects abstractions and moral preening. Unlike liberal internationalists who envision a world evolving toward ever closer cooperation and interdependence, he sees a global arena of relentless competition in which only the strong can dictate terms.

A Tradition of Realism: Mearsheimer’s Intellectual Forerunners.

Far from being an outlier, Mearsheimer’s “realist” outlook builds on the thinking and polices of Americans from the county’s founding to the present.

The Farewell Address of the first US President, George Washington, warned against entangling alliances with foreign countries, and urged a policy of neutrality in overseas conflicts. Written with Alexander Hamiton, the Address served for a century as the foundational charter of a realist US foreign policy.

It was issued in 1796, at a time when revolutionary France was battling a coalition of European monarchies, and the United States – a fledgling republic – was under immense pressure to take sides. Though still technically bound by the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France, Washington had already declared neutrality in 1793 , insisting that the Treaty did not oblige the US to support France’s offensive campaigns. His Address reaffirmed this position, warning Americans of the perils of entanglement in European conflicts: “Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor, or caprice?”

Washington’s strategic caution was more than theoretical – it was forged in the crucible of real events. The Jay Treaty of 1795, which normalized trade and resolved debt disputes with Britain, infuriated revolutionary France, which viewed it as a betrayal. Yet Washington regarded it as necessary for preserving economic stability. The US economy of the 1790s was heavily dependent on transatlantic trade, especially with Britain, and the young republic’s government budget relied heavily on tariffs on British imports. War with Britain would have devastated the American economy. For Washington, neutrality was a matter of national survival.

In his Farewell Address, Washington also recognized the United States’ geographic isolation as a strategic advantage: “Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course … Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation?” This geographic detachment, he believed, made it much easier for the US to chart an independent course, free from the entanglements and rivalries of Europe. It laid the groundwork for later policies, such as those based on the Monroe Doctrine, that reinforced American security through strategic nonalignment.

Washington’s pragmatism reflected a realist ethos. He rejected involvement in overseas conflicts motivated by notions of ideological kinship. He urged restraint and neutrality in foreign wars, warning that alliances risked compromising national sovereignty and dragging the young republic into conflicts that offered no lasting benefit. His emphasis on avoiding “permanent alliances” and “overgrown military establishments” mirrors modern realist concerns about imperial overstretch and the dangers of over-commitment. The first American president may thus be regarded as the “grandfather” of a realist US foreign policy.

George F. Kennan

George F. Kennan (1904-2005), a diplomat and historian, is perhaps best known as the architect of America’s Cold War “containment” policy. He left a mark on US foreign policy above all by turning realist precepts into policy. His call for a US policy of balanced response to Soviet power and influence while avoiding direct military confrontation, first laid out in his “Long Telegram” (1946), epitomized realist pragmatism. Kennan stressed the importance of exercising strategic patience arguing that the United States should counter Soviet expansion by bolstering regional allies and avoiding ideological crusades. He was confident that the much greater economic strength of the US and its allies, and America’s much more extensive social-cultural influence in the world, together with the inherent weaknesses of the Soviet system, would eventually bring an end to the USSR and the Cold War.

While both Mearsheimer and Kennan shared a skepticism of moralistic interventions and a focus on geopolitical equilibrium, their views are not identical. Kennan’s realism diverged from Mearsheimer’s in its emphasis on diplomacy and soft power. While Mearsheimer prioritizes military might and hegemony, Kennan stressed nuanced statecraft, writing that “the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.”

Hans Morgenthau

Hans Morgenthau (1904-1980), often regarded as the father of classic realism, cited human nature as fundamental to understanding international relations. In Politics Among Nations a highly influential work first published in 1948, he argued that states are driven by an innate “will to power” rooted in a universal human desire for dominance.Unlike Mearsheimer, who attributes state behavior above all to a striving for survival in a systemic global anarchy, Morgenthau emphasized psychological and innate human factors.

For Morgenthau, power was both an end and a means, and ethical norms might temper but could never eliminate the struggle for power. His realism was prescriptive as well as descriptive. He cautioned against a moralistic foreign policy, notably opposing the Vietnam War on the grounds that it did not advance any notable American interests. His emphasis on prudence and his skepticism of universalist crusades is in line with Mearsheimer’s warnings against liberal hegemony, though Morgenthau’s focus on human agency contrasts with Mearsheimer’s structural determinism.

Mearsheimer paid homage to Morgenthau’s work in his 2005 essay, “Hans Morgenthau and the Iraq war: realism versus neo-conservatism,” in which he contrasts realist and neo-conservative approaches to foreign policy, citing the 2003 US invasion of Iraq as a case study. Mearsheimer contended that Morgenthau would have opposed that war, much as he opposed the Vietnam War, due to his realist opposition to ideological crusades, and his emphasis on power dynamics, national interest, and the limits of military force.

Beyond the Ivory Tower: Mearsheimer’s Predictive Relevance

Perhaps the best evidence of the enduring value of The Tragedy of Great Power Politics is its prescience. In the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet empire, many Americans happily embraced a triumphalist view of lasting US global hegemony. The late neoconservative columnist Charles Krauthammer, for example, boasted in 1991 that the US was now tops in the world at a “unipolar moment” in history.

Mearsheimer rejected that appealing view. Despite the death of the USSR and the end of the Cold War, he warned in his 2001 work, the specter of great power rivalry would inevitably resurface. He went on to predict that the US would face serious challenges from such Eurasian powers as China and Russia: “Although the United States is a hegemon in the Western Hemisphere, it is not a global hegemon. Certainly the United States is the preponderant economic and military power in the world, but there are two other great powers in the international system: China and Russia. Neither can match American military might, but both have nuclear arsenals, capability to contest and probably thwart a U.S. invasion of their homeland, and limited power-projection capability. They are not Canada and Mexico.”

Mearsheimer understood that even regional hegemons like the United States are still limited in their ability to project power globally. The US, he wrote, “certainly is determined to remain the hegemon in the Western Hemisphere, but given the difficulty of projecting power across large bodies of water, the United States is not going to use its military for offensive purposes in either Europe or Northeast Asia.”

Such warnings were ignored by American leaders, who happily expanded NATO eastward against Russia in the late 1990s. Buoyed by a triumphalist euphoria, Western elites failed to consider that an assertive NATO and an expansionist EU would likely prompt a hostile reaction from Russia. As Mearsheimer later warned in the Russian case, when a great power perceives a growing threat near its borders, it will respond vigorously – if need be, with military force. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, its war in Donbas, and its broader aggression in Ukraine, all validate Mearsheimer’s consistent writings about the enduring reality of great power competition. Moscow’s military actions are not irrational outbursts or ideological crusades – they are strategic moves in a power competition shaped by geography, history, and security needs.

The fundamental dynamics described by Mearsheimer in his 2001 book are still very relevant today. New tools of international conflict – including cyber warfare, drone strikes, large-scale economic sanctions, aggressive computer hacking, information warfare, and artificial intelligence – have emerged in recent decades, but they are deployed in the same age-old contest for dominance and survival.

A Voice of Clarity in an Age of Delusion

Mearsheimer has not escaped criticism. He is often derided as cynical, his worldview dismissed as too deterministic or lacking in moral vision. But perhaps that is because in an age of diplomatic platitudes and ideologically motivated interventions abroad, truth has become subversive.

In The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, Mearsheimer offers no easy solutions. Instead, he holds up a mirror – one that reflects the world as it is, not as we might wish it to be. For that, he is demonized in elite circles, both “liberal” and “neo-conservative,” and ignored by politicians of both major parties. But at a time when global affairs are increasingly unstable, his insights cut through the delusions that plague both academic theory and political practice.

Conclusion: Realism Without Illusions

The Tragedy of Great Power Politics dismantles the illusions of liberal triumphalism and replaces them with a sobering analysis of how power operates in an anarchic international system. His emphasis on “mobilizable wealth” reminds us that geopolitical influence depends not on wishful thinking or quixotic doctrines but on the tangible ability to project force and absorb geopolitical shocks. In that sense, his book is not just a theoretical contribution – it is a survival manual for navigating an increasingly turbulent new century.

Mearsheimer’s perceptive and persuasive outlook, one that is validated by history, provides a fine lens through which to view the often brutal dynamic of great power politics. During an era in which Americans are increasingly polarized, distrustful and confused, his work is a welcome beacon of analytical clarity. Whether or not one agrees with him, ignoring Mearsheimer is an option only for fools.