President Roosevelt’s Secret Pre-War Plan to Bomb Japan

By Mark Weber

Several months before Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt secretly authorized devastating American bombing raids against Japanese cities. A top-secret document declassified in 1970 shows that in July 1941 Roosevelt and his top military advisers approved a daring plan to use American pilots and U.S. war planes – deceitfully flying under the Chinese flag – to bomb Japan’s major cities. / 1

The bombers would be under the command of Claire Chennault, a former U.S. Air Corps flyer who had been in the employ of the Chinese government of Chiang Kai-Shek since 1937. In July 1941 Chennault already headed the “American Volunteer Group” (AVG) squadron of U.S. “Flying Tiger” fighter planes that had been combatting Japanese forces in China. Chennault’s colorful unit was glorified in American newspapers and magazines, and in the 1942 Hollywood motion picture Flying Tigers, starring John Wayne.

Claire Chennault

The young pilots who flew the distinctively “shark-toothed” P-40 warplanes were ostensibly mercenaries, and the AVG force had no official connection with the U.S. government. In reality, the squadron was secretly organized and funded by Washington – in flagrant violation of both American and international law. Set up without consultation or consent of Congress, it violated the U.S. Neutrality Act and the Selective Service Act of 1940. Chennault’s squadron was also a breach of Roosevelt’s own formal declarations of U.S. neutrality in the conflict between Japan and China, which had been raging since 1937.

By aiding China, Roosevelt sought to keep Japanese forces tied up there. So long as the Japanese were fully occupied in China, he thought, they would not be a threat to British and U.S. interests in Asia. If China fell, Britain would have to divert war ships, troops and materiel badly needed in Europe.

A secret memorandum from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations dated January 17, 1940, confirms that almost two years before the Pearl Harbor attack, the Roosevelt administration was considering war against the Japanese with U.S. mercenaries organized in “an efficient guerrilla corps.” The memo also discussed a clandestine U.S. combat air operation against Japanese forces. Some months later, in May 1941, another memorandum for Roosevelt from Admiral Thomas C. Hart, Commander of the U.S. Asiatic fleet, began: “The concept of a war with Japan is believed to be sound,” and went on to discuss how Japan could be attacked by American-piloted bombers. / 2

To put such ideas into effect, Chennault pushed for the formation of a task force of American-piloted bombers under his command that would raid Japan itself. “If the men and equipment were of good quality, such a force could cripple the Japanese war effort,” he wrote. “A small number of long-range bombers carrying incendiary bombs could quickly reduce Japan’s paper-and-matchwood cities to heaps of smoking ashes.”

Chennault’s proposal quickly received the enthusiastic support of China’s ambassador in Washington, T. V. Soong (multi-millionaire banker brother-in-law of Chinese premier Chiang Kai-Shek), British ambassador Lord Lothian, U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau.

The idea to bomb Japan was first formally presented to Roosevelt on December 19, 1940. The President’s response was to exclaim “Wonderful!,” and to immediately instruct his Secretaries of State, Treasury, War and Navy to begin working out the details of a battle plan. / 3

Not everyone was so enthusiastic, though. Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall expressed misgivings. Marshall cautioned that having American pilots bomb Japan using American planes with Chinese markings was a deception that would not fool anyone, but would simply plunge the United States into a war with Japan at a time when the U.S. was not yet prepared.

As a result of such misgivings, the plan was temporarily shelved. A few months later, though, a somewhat modified version was revived as “Joint Army-Navy Board Paper No. 355.” / 4

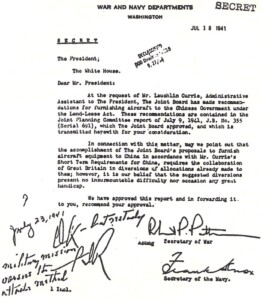

Cover letter of the “Joint Army-Navy Board No. 355” paper authorizing American bombing raids against Japan – more than four months before the Japanese attack against Pearl Harbor. This top-secret document is signed by the Secretaries of War and Navy, and bears Franklin Roosevelt’s initials of authorization and his handwritten date, July 23, 1941.

As finally laid out in JB 355, an air strike force of 500 Lockheed Hudson bombers was to be organized as “The Second American Volunteer Group” under Chennault’s command. Its mission would be the “pre-emptive” bombing of Japan. The strategic objective of JB 355 was the “destruction of Japanese factories in order to cripple munitions and essential articles for maintenance of economic structure in Japan.” From bases about 1,300 miles away in eastern China, the American bombers would strike Japan’s industrial centers, including Osaka, Nagasaki, Yokohama and Tokyo. (These air strikes would have unavoidably claimed the lives of many civilians. By contrast, the Japanese planes that attacked Pearl Harbor carefully avoided civilian targets.)

U.S. funds for the operation were to be provided as part of a general loan to China and channeled through a dummy corporation. The American military personnel involved were given deceptive passports. (Chennault’s gave his occupation as “farmer,” and cited him as an “advisor to the Central Bank of China.”)

Secret plan JB 355 was approved by the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, and – on July 23, 1941 – by President Franklin Roosevelt.

No one played a more important role in promoting and organizing this plan than Lauchlin Bernard Currie, a close Roosevelt White House adviser. Years later the 89-year-old Currie provided details of his role in the secret operation and of Roosevelt’s support for it in an interview at his home in South America. / 5 A major motive behind Currie’s eagerness to get the U.S. into war with Japan may have been his strongly pro-Soviet sympathies. There is even tantalizing but inconclusive evidence to suggest that Currie was a Soviet agent. / 6

When Roosevelt approved plan JB 355, Currie sent a secret cable to Chennault: “I am very happy to be able to report that today the President directed that 66 bombers be made available to China [sic] this year, with 24 to be delivered immediately.”

Lauchlin Currie in 1939

Although it had been approval by high-level officials, the plan was not well conceived. In the view of Yale University history professor Gaddis Smith, the Lockheed Hudson bombers that were to carry out the raids would have been easily shot down by Japan’s first-rate fighter planes. / 7

Two days after approving JB 355, Roosevelt declared a crippling trade embargo against Japan, an act of economic strangulation that he knew would virtually assure war. (At that time, about 90 percent of Japan’s oil and iron came from the United States.) And having broken Japanese codes, British and American officials learned in early July of Japan’s intentions in the Pacific: war with the U.S. was now all but inevitable. / 8

Understandably viewing Roosevelt’s campaign as a mortal threat to their country’s very existence as a modern industrial nation, Japan’s leaders resolved to strike a first blow. They reasoned that by destroying the U.S. Pacific fleet in Hawaii in one decisive surprise attack, they would remove the single greatest obstacle to forging a self-sufficient Japanese empire in eastern Asia.

History thus intervened to thwart Roosevelt’s plan to bomb Japan. Before JB 355 Japan could be put into effect, and before Japan felt the full impact of the US trade embargo, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor – and Roosevelt had the open war with Japan that he had anticipated. In effect, Japan beat America to the punch. Four days after the Pearl Harbor attack, all further action on the JB 355 plan was suspended, and the bomber pilots who had been recruited were quickly incorporated into the regular U.S. armed forces.

Franklin Roosevelt branded December 7, 1941, as “a date which will live in infamy.” And although many millions of Americans still regard Japan’s “sneak attack” as the ultimate act of international deceit and treachery, it was hardly unique.

In 1801, Britain’s Lord Nelson destroyed Denmark’s fleet in a surprise attack on Copenhagen. In May 1846, the U.S. Army invaded Mexican territory before Congress got around to declaring that a state of war existed with Mexico. Far from feeling ashamed about it, Americans later elected as President the commander who lead the expedition, Zachary Taylor. In June 1967, Israel’s surprise attack against Egypt was widely praised in the U.S. for enabling Israeli pilots to destroy almost the entire Egyptian air force while it was still on the ground.

Just about every major power has resorted to surprise attack at one time or another, according to a study by British senior army officer and historian Sir John Frederick Maurice. Between 1700 and 1870, he calculated, France carried out 36 surprise attacks, Britain 30, Austria twelve, Russia seven, Prussia seven, and the United States at least five / 9

The long-suppressed story of Roosevelt’s plan to bomb Japan deserves to be better known. As sensational as it is, though, it is only one chapter of the larger – and still little known – story of the US President’s extensive and illegal campaign to bring a supposedly neutral United States into the Second World War. / 10 Indeed even before the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, he was secretly trying to incite conflict there. / 11

In the months before the Pearl Harbor attack, the American president accelerated his illegal campaign. For example, after Axis forces launched the fateful June 22, 1941, “Barbarossa” attack against Soviet Russia, he promptly began sending American aid to Stalin. On July 25, 1941, Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets in the United States, thus ending trade relations. He closed the American-run Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. In June and July 1941, he dispatched U.S. troops to occupy Greenland and Iceland. And by September-October 1941, U.S. warships were actively engaging German U-boats in the Atlantic, in flagrant violation of U.S. and international law./ 12

The magnitude of Roosevelt’s undercover military operations against Japan and Germany, at a time when the U.S. was ostensibly neutral, dwarfs other, much ballyhooed clandestine U.S. military operations in later years, such as President Reagan’s help to the Nicaraguan “Contra” fighters, or the infamous Iran-Contra operation.

Notes

1. Much of the information for this essay is from: Don McLean, “Tigers of a Different Stripe: FDR’s Secret Plan to Torch Japan Before Pearl Harbor,” Soldier of Fortune, January 1989, pp. 66-93; ABC television “20/20” broadcast, “FDR’s Planned Preemptive Attack on Japan,” Nov. 22, 1991 (No. 1149).

2. D. McLean, Soldier of Fortune, Jan. 1989, pp. 67-68, 91.

3. Duane Schultz, The Maverick War: Chennault and the Flying Tigers. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987. Cited in: D. McLean, Soldier of Fortune, Jan. 1989.

4. Joint Army-Navy Board Paper 355 (“Aircraft Requirements of the Chinese Government”), July 1941, Serial 691, National Archives, Washington, DC.

5. ABC television “20/20” broadcast, Nov. 22, 1991.

6. D. McLean, Soldier of Fortune, Jan. 1989, pp. 70-71.

7. ABC television “20/20” broadcast, Nov. 22, 1991.

8. John Costello, The Pacific War (1981); John Toland, Infamy (1982); Percy L. Greaves, Jr., “Three `Day of Infamy’ Assessments,” The Journal of Historical Review, Fall 1982, pp. 319-340.

9. William H. Honan, “Nightmare at Port Arthur,” Naval History (U.S. Naval Institute), August 1990 (Vol. 4, No. 3). Source cited: John Frederick Maurice, Hostilities Without Declaration of War [from 1700 to 1870], London: HMSO, 1883

10. Mark Weber, “Collusion: Franklin Roosevelt, British Intelligence, and the Secret Campaign to Push the US Into War.” Feb. 2020 ( https://ihr.org/other/RooseveltBritishCollusion ); William H. Chamberlin, America’s Second Crusade (1950 and 2008); Charles C. Tansill, Back Door to War (1952); Charles A. Beard, President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War 1941 (1948); It’s worth noting that the ABC television “20/20” broadcast of Nov. 22, 1991, on the JB 355 bombing plan, failed to put the story in the larger context of President Roosevelt’s wider, secretive campaign to bring the U.S. into war.

11. Mark Weber, “President Roosevelt’s Campaign to Incite War in Europe,” The Journal of Historical Review, Summer 1983, pp. 135-172.

12. For a more detailed review of such acts, see: George Morgenstern, Pearl Harbor: The Secret War (1947 and 1991); pp. 87-88; William H. Chamberlin, America’s Second Crusade (1950 and 2008).

From The Journal of Historical Review, Winter 1991-92 (Vol. 11, No. 4), pages 503-509. Updated and slightly revised, Feb. 2025.