My Life and Role With the German American Bund: A Memoir

By August Klapprott

From 1936 to December 1941, August Klapprott was a prominent figure in the German American Bund, an association of US citizens of German ancestry who proudly expressed admiration for Hitler’s Germany.

As hostility against the Third Reich grew in the US, the Bund and its leaders came under ever more vehement attack – verbal, legal and physical. Their admiration for Hitler’s Reich seemed to validate the often-repeated accusation that the Bund was a “fifth column” tool of the German government or the regime’s National Socialist Party. (In fact, the association received no financial or verbal support from Germany.) As Bund activities and statements by some of its leaders proved increasingly embarrassing to the German government, which sought to maintain good relations with the US, in 1938 authorities in Berlin forbade German citizens to be members.

August Klapprott was born in 1906 in a village in the Lower Saxony region of Germany. He moved to the US in 1927, and became an American citizen in 1933. He served as the Bund’s New Jersey leader, 1936-1941. For six years, he was held behind bars, including as a co-defendant in the high-profile “Sedition Trial” of 1944. He died in 2003, and is buried in Bergen County, New Jersey.

In October 1987, the 81-year-old Klapprott, together with his devoted and energetic wife, attended a conference of the Institute for Historical Review in Irvine, California. The text of his presentation to that gathering, below, was read by Harold Mantius.

In this paper, Mr. Klapprott looks back on his life, and especially his role in the Bund and the vicious campaign against him and other dissidents during the 1930s and 1940s. He explains the experiences and outlook that moved him to take a stand in defiance of the policies and outlook of the US government, the attitude of the mainstream media, and general public opinion. Regardless of one’s view of the Bund and its legacy, this memoir by one of its most important leaders is an informative historical document.

The original text of this paper has been edited for clarity and to correct misspellings and a few minor errors. Supplemental information has been provided in brackets and endnotes.

Ladies and gentlemen! It is quite an occasion to be with you today; and to be permitted to speak of my life’s struggles and sufferings in this country as a disenfranchised citizen of German ancestry. I believe it is appropriate that I address such an audience. For the pressures that have been brought to bear on the Institute [for Historical Review] are reminiscent, in many respects, of the pressures brought to bear on the German American Bund. And, the illegal persecution of leading Bund members, though far more severe, bears similarity with the trials and tribulations that some members of the Institute have been forced to endure. It is my hope that I can shed some additional light on the malicious nature of the forces you now confront – a malevolence clearly manifested in the bombing of the Institute a few years back. /1

To begin with, I must first tell a little about my youth in Germany, during and immediately following World War I. As a boy, from eight to twelve years old, the war raged, and my father was away as a soldier. In fact, in [Brochthausen] our village of 700, there were no men – just women and children. Along with my invalid grandmother, my mother had seven children to feed, so there were nine at the supper table.

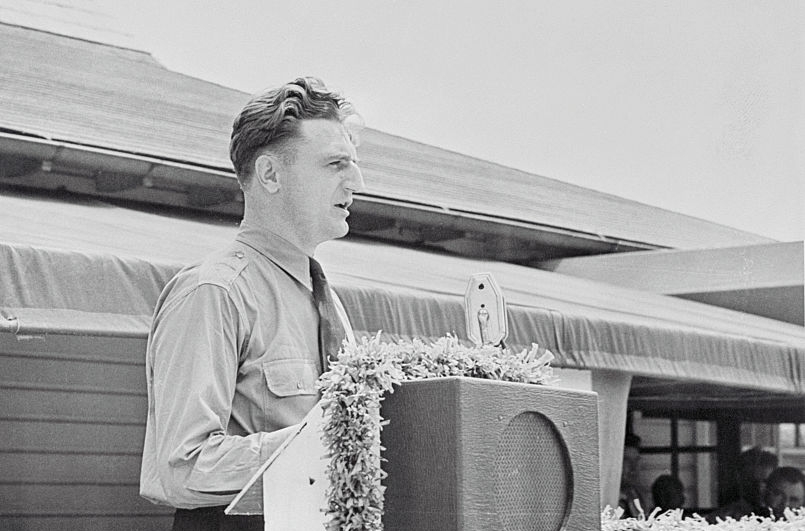

August Klapprott speaks at the Bund’s Camp Nordland, July 1940

Strong in bone structure, I soon became the breadwinner for our clan. I worked for a nearby woman farmer, helping her before and after school, and during the summer vacation. As payment, I received food. My mother would thank the Lord when I brought home the ingredients for another meal, as food was scarce and we were always hungry. (Even after the war, we had to endure two more years of misery and hunger caused by the continuing British blockade of Germany.) I remember my hands shaking from overwork as I did my homework by the light of a candle. Luckily, I had little trouble with the German language, and soon knew all the poems in the textbook by heart. Poetry was my favorite subject. (Along with National Socialism, it is still my passion).

When I was fourteen and a half, a decision had to be made whether I should learn a trade or go on to higher education. The priest in town, my teachers, and my mother favored the latter course, and a scholarship was secured. However, after hearing my father, who had returned from the war with gas in his lungs, arguing with mother to the effect that I would be depriving my brothers and sisters of food should I go to school, I decided to go with father and learn the trade of masonry.

Forced to look for work outside the village, we soon packed up and left home. My father was, up to that time, a perfect stranger to me, but he was a good teacher of the trade. I learned from him the importance of good concentration in order to build something which is at first only an idea. Having pride in the quality of your work was also part of father’s teachings. From my mother’s side, on the other hand, I acquired an insatiable desire to learn from books. My father resented that side of me, and often prophesied that I would get into plenty of trouble someday if I knew too much!

We were working in Bochum in 1923 when the French army occupied the Ruhr valley and Rhineland sections of Germany. The French were busy shipping the piled-up coal to France, while we could not buy a single piece to heat the room father and I lived in. Another young fellow and I got the idea of digging our own coal at night. Handcart ready, with shovels and picks, we went off to the site where others in need of coal had dug before. We were filling our cart in the dark when, from out of nowhere, the well-known call of “Halt, whoever you are!” came from a French patrol. We had already laid out escape routes beforehand. Leaving tools, handcart, and precious coal behind, we went our separate ways down a bushy hill toward the city. My partner in crime did not make it unscathed. He got hit through the right leg, while the bullets passed by my ears – too close for comfort!

Some time later, I got shot at again while on legitimate business for my boss, this time by German Marxists. Bochum’s Communists, operating under the cover of the French occupation, were setting fires throughout the city and terrorizing the population. For two long weeks they held the city’s firemen as prisoners in their firehouses. Then, after the smoke and stench had become unbearable, the French permitted a German Freikorps unit from the south of Germany to come in and combat the Bolsheviks. / 2 Without shooting a single revolutionary, they quickly restored order in the town – which really should have been handled by French occupation forces.

Working every day, but still getting poorer, father and I planned to go home for Christmas. I stood in line for four weeks trying to get a visa from the French. A terrible homesickness had overcome us. About a week before the Christmas holiday we were issued a pass, or so we thought. However, upon reaching the city of Hamm, we were told that the pass was worthless. Back to Bochum we traveled, and back in line I stood in the freezing cold for a passport. Like an angel of mercy, a French officer tapped my shoulder from behind, and told me he had seen me standing in line for weeks. He invited me into his warm office, and I told him my story – that my mother, brothers and sisters, lived in Germany 300 kilometers away, and that father and I had come here to work before the French occupation. I remember the tears streaming down my face while the officer served me a hot cup of tea. It was the morning before Christmas when he gave me a pass to go home. He swore that this time it would let us through.

My father had to borrow money from our boss to pay for the new fare, and it was on Christmas morning, around 4 a.m., when we finally arrived home, totally exhausted after stomping 20 kilometers through fresh falling snow, for we had missed the shuttle train to our village. My mother said that God had been with us all the way, but in spite of the many churches in Germany, there seemed to be no God at all.

Thoughts of leaving the country to earn a living somewhere else, and thereby to help support my mother, first entered my mind in that winter of 1924. My father died in 1925, and the misery got much worse. A female cousin of mine had emigrated to the US, so I wrote to her in New York. She provided a sponsor, and I applied for a visa at the American consulate in Bremen. Twenty-one years old, I entered New York harbor legally on September 19, 1927, full of enthusiasm. For two years I was able to help my mother financially. Then came the bank crash of 1929, and there was no longer much work available in the building profession.

After what I had been through in Germany, surviving the depression was nothing new to me. Then, in 1933, Franklin Roosevelt became President. By this time, the climate [mood] of the country had changed perceptibly. Not only in the workplace, where the shortage of work forced many labor union members to become scabs just to survive, but also in the nation, by and large. Animosity openly directed against Germany in the media, for instance, soon infected the attitude of many in the general population. (At the boarding house where I resided, men would often call me “Son of a Hun,” in hateful ways. I often thought: “How is this possible?” These were all handsome looking men who could have been my brothers. But hate was implanted in their stupid behavior.)

If you will recall, Jews declared war on Germany that same year. / 3 Naive as I was, I waited for someone to arrest these war-declarers. After all, doesn’t it say in the Constitution that only Congress can declare war? I then realized that these people must, indeed, have tremendous influence in the government to get away with such illegal activity. I began to investigate, comparing what was written by patriotic German writers to what was being fed the American people in the media.

In 1934, I became an American citizen, and I also signed over to my second-born brother all of my property rights in Germany. (Since I was the oldest boy in our family, I would have automatically become the owner of our little house upon my mother’s death.) Shortly thereafter, I joined an organization called Friends of New Germany, which was later to become, in 1936, the German American Bund, under the leadership of Fritz Kuhn. This I did, foolishly thinking that I could help spread the truth and work for peace and understanding. For, unknown to most Americans, a vicious anti-German campaign had set in.

Until then I had played soccer in the German American Soccer Association. I had expected, upon joining the Friends of the New Germany, that many of my soccer club members would follow. Not many did so. However, my wife of 52 years, whom I had first met on the sidelines and at soccer club dances, subsequently became involved in the youth movement of the Bund. Anyway, I soon became so busy in my new surroundings, that I stopped playing soccer altogether.

Our meetings, held for the most part in rented halls, were frequently attacked by Meyer Lansky’s Bolsheviks. / 4 (Four of our men were found dead, in and around New York – to which I can attest personally – all clubbed from behind on their way home from meetings, or from work.) So, we were soon forced to organize our own Order Division. In uniform dress, consisting of black boots, white shirt and swastika armband, we became quite effective at protecting our meetings. (It should be noted that at no time was anyone permitted to carry weapons, not even pocket knives. We relied solely on physical fitness, and routinely practiced calisthenics).

Under Kuhn’s leadership, we formed over a dozen such units in New York City and New Jersey alone. Likewise, we founded youth groups, drum and fife corps, and ladies auxiliaries. The Bund, based on a spirit of ethnic pride, was starting to grow. I soon became deeply interested in our self-defense formation. From plain member, I advanced in 1935 to Unit Leader of Hudson County, N.J. (That county was Frank Hague’s domain. Hague, if you recall, was the perpetual mayor of Jersey City, who, by the time of his death, had accumulated roughly five million dollars with an annual salary of only eight thousand.)

It was during 1935 that a member summoned me to West New York, N.J., to witness the film making of Kristallnacht, exactly as it was to have happened three years later in Germany! / 5 We asked the police whether or not these Hollywood brown-shirted storm troopers, kicking crying old Jews around in front of their alleged stores, with broken glass all over the sidewalks, and their possessions thrown onto the street, had permission from the town. It turned out they had no permit to make such a film, and were forced to leave, film in hand. How stupid we were. Nothing was actually achieved. They still had their illegal film to poison people’s minds and to raise money for their crusade against Germany!

In 1936, I married [Hedwig], and Fritz Kuhn appointed me to the post of New Jersey District Leader. Soon thereafter, we procured a piece of property to be used as a center for the Bund’s social activities. Everything was done legally, and Camp Nordland, as it was subsequently named, was incorporated under the name of German American Bund Auxiliary, a New Jersey corporation. The necessary money was raised by issuing Certificates of Indebtedness. The lowest single amount was arbitrarily set at $25. As I remember, the highest ever given out was a $600 certificate. The money came entirely from members of the German American Bund.

To the listener today, I can state quite frankly that I personally knew every one of the investors. I knew where they were employed, or where their small businesses were located. The charge that the money for buying and improving 205 acres of Sussex County [New Jersey] property came from Hitler was an outright lie. For three years we were able to fight off the eternal haters.

Then, in 1940, the New Jersey legislature disenfranchised our corporation, shortly after we had received a property tax bill for an estimated $86,000. Of course, the lawmakers never had the courage to investigate whether the allegation was true or not before voting to satisfy the “holy” warmongers.

We also ran into a highly crooked sheriff of Sussex County. He was a bootlegger, making and selling illegal booze. Of course, the “hidden hand” knew all about this. That’s why this sheriff was ordered to raid the camp one morning, with a search warrant signed by a Newton, N.J., judge, to look for, of all things, “indecent literature.” Luckily for us, a single, honest deputy had phoned the camp at 12 o’clock the night before, informing me that six carloads full of deputies would raid Camp Nordland at about 7 a.m., and would plant the “indecent literature” they were looking for! I must have been on the phone for an hour calling for help, and 25 of our people managed to come up that night from the cities and towns where they lived.

Our men kept a close eye on the deputies when they arrived on schedule. I stuck with the head of the pack as they went from building to building. I had noticed that in each of the cars a deputy had been left behind with a package of sorts, so I assigned six of our brightest men to watch those conspirators. And so, the distribution of whatever literature they had brought to assassinate our character never took place.

Frustrated, the sheriff’s party then went to the youth camp, which had been closed since the end of summer, and filled two bushel baskets with assorted paraphernalia (little flags, insignias, youth armbands, and even a few American flags). They also confiscated a .22 caliber rifle, used by counselors to shoot copperheads. It had been locked in a kitchen cabinet, which I opened with a key upon request. After four hours of searching every nook and cranny of the camp under the watchful eyes of the men of the Order Division, they decided to bring their booty to the judge who had issued the search warrant.

In the Newton courthouse, I lifted every item in front of the judge and asked: “Is this indecent literature?” About fifty times, with anger and frustration upon his face, he had to answer “No.” I then asked for permission to take everything home with me, and permission was granted – that is, except for the rifle, which he kept “for further investigation.” (Later, in 1941, according to the press, this same rifle shot 20 miles over mountains and valleys into a Hercules Powder plant, and caused an explosion resulting in the death of 26 men. Leaving aside the fact, that a .22 cal. rifle could not possibly shoot that far, the press did not consider it noteworthy to inform the public that the judge had kept the rifle, and that it was in his possession, not ours, at the time of the accident.)

As you may know, Bruno Richard Hauptmann was executed in 1936 for kidnapping Charles Lindbergh’s baby. He had been convicted primarily on the weight of Lindbergh’s testimony. Put on the witness stand, he swore – because his weak wife and the morbid crowd demanded it – that he could identify Hauptmann’s voice as the one he had heard in a dark Bronx cemetery two years earlier! (Is this humanly possible?) That testimony nailed the German-born Hauptmann, because everything else was a circus, at best. (Oh, about that ladder. When I addressed our members, I always asked the same question. Why doesn’t Hauptmann’s drunken lawyer send the prosecutor up that dilapidated piece of junk boards with 20 pounds of bricks, and put an end to this farce?)

It must never be forgotten that this trial did more to advance the cause of anti-German warmongering in America than any other single event, a fact which is ignored all too frequently in the popular literature. For example, Anthony Scaduto, in his book about the case, Scapegoat, almost entirely overlooks the prevailing hysteria created by the press. And Ludovic Kennedy, in The Airman and the Carpenter, likewise does little to touch upon the hopeless atmosphere of anti-German hatred which led to the murder of Bruno Hauptmann, and so many innocent millions later. The perpetrators of this “travesty of justice” are still in power, as everyone well knows, busy at work building Holocaust monuments and persecuting innocent Europeans as “war criminals.”

In 1934 I left the Catholic Church because it too had started a hate campaign against Germany. I have no time here to explain my decision to change my religion. At the time it was a hard decision for me to make. But, as things developed, I’ve had no reason for regrets. To the contrary, I became a free man as the years went by, whether in American jails or outside of them.

In 1937 the German airship Hindenburg flew over New York. I stood on the Palisades in Weehawken, N.J., and watched as it turned south toward Lakehurst. It was a beautiful, cloudless day. An inner vision of doom made me throw up my arms and cry out: “Go back you magnificent fools. Go home instead of landing here.” The people around me, with grimaced faces, probably thought that I was as crazy as a loon. But that is how deeply I could sense the atmosphere of hatred emanating from the news media, soon to be crowding the landing fields with their cameras. (Tom McMorrow, a New York Daily News columnist, years later mentioned in his column that as a young reporter at Lakehurst that fatal day, he had asked an older colleague why there were so many reporters present. “Are there prominent people on board?” “Oh no,” he answered. “We want to see it blow up.”) In the late afternoon [of May 6], my feeling of impending doom was confirmed over the radio in vivid broadcast descriptions.

Some 20,000 men and women attended the Bund-organized rally at Madison Square Garden in New York, Feb. 20, 1939

Great successes had been achieved by the Bund in just a few short years, and Bund gatherings grew in size. They were frequently the scene of violent confrontation with the enemy. I noted that most of our paid speakers were easily rattled on such occasions, so it was absolutely crucial to maintain order and not allow things to get out of hand. In the big battle of Yorkville Casino in 1938, 200 Jewish-led Communists had infiltrated the hall that seated roughly 2,000 people. As was often the case, I was in charge of the men of the Order Division. When the catcalls started, and the throwing of beer bottles commenced, I immediately grabbed the microphone and gave the order to clear the hall of the riffraff.

It took our men about 20 minutes to toss the bums down the stairs out on to 86th Street. Here, some of the fakers put on War Veteran caps and smeared ketchup on their faces for effect. And, Life magazine was there to take pictures. / 6 “Nazis Attack American War Veterans,” screamed the headlines. And again, the whole affair was staged by the “media masters.” No one there was seriously hurt, for our men were trained to establish control, not mete out unnecessary punishment.

Here, I must praise the New York City Police Department. These men were staunch, if silent, allies. With all the fury and congestion on 86th Street, they waited to confront us until after our men had reset every chair, and tranquility had been restored to the vast Casino Hall. The Captain of the precinct, along with two high-ranking officers, came in behind the stage to ask me about the alleged fight someone had reported. I told them: “Look for yourself. There is no fight around here.” They just smiled, saluted, and went away writing something in a notebook. The same perfect behavior on the part of the New York City police must also be reported during the Bund’s George Washington Birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden in 1939. / 7

A large gathering in New York City organized by the Bund to honor George Washington, Feb. 20, 1939

I was again in charge of security. We had filled the big hall to the last seat. The police had cordoned off two blocks around the Garden, to prevent access to all except those with tickets. Two hundred reporters had requested and received free entrance, and were seated at the side of the stage. With them came the little Jewish would-be assassin, who later, when he attempted to attack Mr. Kuhn with a knife, came sliding in front of my feet. Our own men, around the speaker’s lectern, had saved Kuhn’s life, and the police led him away in handcuffs. (This scene can be seen in the film Swastika.) As soon as the hyenas of the press, who had come to see blood, saw this plot fail, they became very unruly. A woman wearing a large hat was spewing out four-letter words for a minute or so, which moved me to call over two policemen to lead the troublemaker away. (The next morning, I learned that we had removed Dorothy Thompson, the liberal darling.) Once she was led away, those who remained all behaved quite normally. Later that evening, mounted police literally saved my life, when a howling Jewish mob broke through the barricades and tried to overturn my station-wagon, which was loaded with assorted paraphernalia.

This greatest success would eventually lead to the downfall of Fritz Kuhn and the Bund. The all powerful Jewish “Kahilla” had decided to break our necks and advance their war against Germany. Thus, the indictment and conviction of Kuhn followed logically. He was sentenced to two and half to five years in prison for allegedly stealing money from the Bund. A Jewish “committee” found this out. Of course, they were not in the least concerned about someone stealing money from our organization. This was simply a convenient, transparent pretext to bring legal action against the Bund. And, as a reward for convicting Kuhn, Thomas Dewey, the small-minded New York City District Attorney, later became Governor of New York state.

German-American Bund parade on East 86th street in New York City, Oct. 30, 1939

Fritz Kuhn finished his sentence in the Dannemora state prison in New York, shortly before the war’s end in Europe. He was officially stripped of his citizenship and sent to West Germany. There he was treated as a “war criminal” and put into a concentration camp – from which he subsequently escaped, only to be recaptured. He died under the miserable conditions of postwar Germany. Does anyone wonder that I spent nearly $10,000 to regain my American citizenship, which was illegally taken from me by a New Jersey Federal Court in 1942 while I was being held under criminal indictment in New York.

For all practical matters, the Kuhn conviction destroyed the Bund. Eight hundred members of the largest unit in Brooklyn broke away and founded the American National Socialist Party, of which after a few short months nothing was ever heard of again. Those people also stormed the National Office, attacking us for having done too much for Kuhn, while others came in demanding that we appeal his conviction. What bothered me most was that the court proceedings seemed to show that Kuhn had indeed helped a “blond bombshell,” without telling anyone about the affair. I took the following stance: “He who can throw stones [?] should step forward to accuse. Believe in the ideals of the movement, look ahead to the coming war, and prepare yourself for it.”

It was during this period, it should be noted, that I had to work at the National Office in New York on our newspaper [The Free American / Deutscher Weckruf und Beobachter]. That’s because I had been personally bankrupted when the New Jersey state government disenfranchised the Nordland incorporation. I remember very clearly the first Sunday after that illegal act. Several hundred people had come to Camp Nordland, demanding answers to a thousand unanswerable questions. All of a sudden, our crooked local sheriff arrived to threaten our people with arrest should they not leave immediately. I told the gathering that all those who still had a job should not foolishly go to jail. Meanwhile, activists of a Jewish group from Newark were busy writing down automobile license plate numbers, unhindered by the sheriff’s men. (That sheriff, who had caused us so much trouble, was eventually indicted and convicted of all sorts of criminal activity.)

For some time I had occasionally written short pieces for our weekly newspaper, which expressed my inner feelings. I always considered others more masterful in this respect, however. Now, I had been catapulted into a position I knew little about. Mr. Frederick Schader, a professional journalist, edited the paper’s English-language section. My job was to edit the German-language section and, in addition, to write a brief editorial. I believed that I had been given that position on the newspaper because Mr. [Gerhard Wilhelm] Kunze, who had been elected National Chairman in 1940, and others, felt that I needed a weekly salary of at least $35 to maintain my family. For amid all this turmoil, my daughter had been born on June 12, 1940, at Christ Hospital in Jersey City. My wife and I named her Sieglinde, the mother of Siegfried in Germanic folklore.

When the morning arrived to bring my wife and child home from the hospital, I called National Headquarters to secure a loan, but later that day, like a miracle, the mailman brought me a tax refund check of more than $300 for the year 1938, more than enough for the purpose at hand. I mention this here to record that we paid our taxes. From that day on, the milkman delivered to our back window two quarts of milk every morning, for which he refused to be paid.

In our New York office, I soon became a kind of “lightning rod” for people who came storming in. I was in a visible position, while Wilhelm Kunze mostly stayed in his private office. Mr. [Wilbur] Keegan, the New Jersey lawyer whom the Bund had retained since the Kuhn trial at a cost of $100 per week, had also moved in. I strongly disapproved of this. It soon became apparent that it was he who was really running things. Keegan frequently called the FBI to inform on our every move. I mistrusted this whole course of action, whereas Kunze and the others welcomed it. The only way I could protect myself against entrapment was to remain elusive. For example, every Monday I traveled to Philadelphia to have our newspaper printed by [William B.] Graf & Sons. Although the FBI was already made aware of this, I made a point of never indicating the mode of transportation, nor when I would leave and return.

It was during an executive session early in 1941 that Wilhelm Kunze declared that he no longer believed in the possibility of success. I took this as a sort of a joke. “What else is new?,” I asked. Shortly thereafter, he vanished, and no one knew where he went. Only later was I able to piece things together. From the Midwest, he left the country for Mexico. I now know the real reason for this, but I will not divulge as it would hurt too many people who are still alive.

From that point on, I received orders from comrade [George] Froboese in Milwaukee, who was the only ranking member with seniority over me. He remained in Milwaukee, leaving Mr. Keegan, the lawyer, Mr. [William] Luedtke, the National Secretary, and myself in charge of the National Office in New York. It was during that time that I began to develop stomach problems. I subsequently visited Dr. Bergmeier in West New York, who diagnosed it as a stomach ulcer. He prescribed peace and quiet, and no more excitement for awhile. But to no avail, as a Mr. [William Roulon] Paxman and his FBI assistants pestered me and my family endlessly.

On the Friday before the Pearl Harbor attack [Dec. 7, 1941], the Supreme Court of the State of New Jersey threw out the law – declaring it unconstitutional – under which nine of our people from Camp Nordland, including myself, had been sentenced to two years in jail. This obscure law made it a crime to speak badly of the Jews. Our defense argument had been that if Jews had the right to libel us, then we had the right to defend ourselves by exposing their activities. The day after the decision was handed down, Mr. Keegan and I went to Newton, N.J., to confront the judge who had sentenced us. We intended to ask him for the return of the $18,000 we had put up as bail, pending appeal. Not finding him at the courthouse, we eventually found him in a clubhouse on a golf course. There Mr. Keegan took him aside and spoke with him for a while. When he and I met again, he told me that the judge informed him that the FBI had taken the money, claiming that it came from Hitler. Needless to say, we never saw that money again.

I should also mention that during the raid on National Headquarters on December 9, 1941, [Henry] Morgenthau’s Treasury Agents stole the list of contributors to our bail fund. Fortunately, that list contained only initials. That’s because after Kuhn’s conviction, the Bund begun erasing all names of members in its files, and worked only with initials. Lists of contributors were handled in a similar manner. Only the unit leaders were able to identify those who had contributed. All this had been done to protect our people.

The German American Bund, it must be stressed here, not only held meetings and demonstrations. It worked quietly in many fields of education, such as conducting German language classes for our children. We were also very active combating the Jewish boycott of German goods. We held several big Christmas markets in the New York Coliseum, organized by the Konsum Verband [consumer’s association], another Bund auxiliary. We had a sort of “Green Stamps” system, whereby participating small German American businessmen gave these stamps to their customers, who pasted them in a book. When each book was full, it could redeemed for one dollar. In that way, many of our people were able to stay in business until the war years. In fact, many got their start at this time, and some have since grown to be mighty big – but have conveniently forgotten those who had helped them to get off the ground.

All Bund activities were controlled through our National Offices, headquartered in three rented rooms, one flight up, on the corner of 85th Street and Third Avenue in Yorkville [district of Manhattan]. Right after the Pearl Harbor attack, it should be noted, we voluntarily halted all our activities. We tried to do this in an orderly fashion, and would have done so had we been permitted. However, on December 9, 1941, agents of the Treasury Department raided the Bund Headquarters. Looking more like East-side bums rather than government agents, they thoroughly wrecked the place and manhandled our people. They even stole my personal attaché case, which was never returned. I should like to mention that other prominent people, such as Mr. Robert Wood, head of the giant Sears, Roebuck company, were also treated in similar fashion by Morgenthau’s men.

Legal battles followed quickly after the raid on the Bund’s national offices. The first of these was the infamous Hartford trial [June 1942]. During that ordeal, three members of the Bund, along with several other individuals, were charged with having conspired against the government of the United States during the summer of 1941. The case revolved around a Russian Count with the name of [Anastase] Vonsiatsky. / 8 He had fled Russia in 1920, and subsequently married a wealthy widow of a railroad fortune. He allegedly gave Kunze the necessary money to go to Mexico. Kunze had apparently promised that he would do his best to secure him a position in a future Russian government, to be established under German occupation. To say the least, both men were guilty of engaging in an absurd reactionary fantasy. One often wonders what little boys grown men can be when they have riches but no brains. However, be that as it may, since America was not at war in August of 1941, these men could not logically be charged with conspiring against the United States.

The whole story is so unbelievable that one could cry openly for everyone involved. A priest, hired by the FBI to entrap us, had started this legal campaign. Luckily for me, I was just leaving for Philadelphia when this man arrived at the Bund’s national office. In my absence, he approached Kunze, claiming that with his international connections, and with the protection of his garment as a priest, he could help finish off the Communists. Only dreamers could believe in such an idiotic possibility. Anyway, this strange looking priest also expressed interest in meeting Count Vonsiatsky. Thus began the story that ended in prison sentences for the unfortunate innocents involved.

It should be noted that every defendant [in the Vonsiatsky case] pleaded guilty on advice of counsel. I told the prosecutor that should I be indicted, under no circumstances would I plead guilty to this farce. And, to my surprise, they let me go! I know today, that everyone indicted in Hartford should have put up a strong legal fight, and that Keegan, our own lawyer, was primarily responsible for the guilty pleas. No doubt, the FBI held the “Sword of Damocles” over his head, and he wanted to save his own neck.

In March of 1942, I suffered a sudden convulsion of blood during the middle of the night, and fell unconscious on our bedroom floor. My frantic wife immediately called an ambulance, as well as former Bund activists to ask for blood transfusions. More than fifty former members arrived during the night, offering their blood, and thereby exposing themselves to possible further persecution. About noon the next day, after receiving two pints of donated blood, I awoke to hear a nurse call “Doc, Doc! Come here. This guy is waking up, by God!” I felt her lift my right arm from under the covers, which I was powerless to do myself. With only about 30 percent of the blood necessary to function properly, I was released from the [Christ] hospital with a statement that I could not be operated on because of my weakness. However, that did not prevent the FBI from continuing its campaign of constant harassment against me and my family. When I was arrested on July 7, 1942, on a new set of conspiracy charges, I felt somewhat relieved, thinking that the unending hassle would at least be over.

Flag-raising ceremony of Bund youth at Camp Nordland in New Jersey, July 21, 1937

The trial was to take place in New York City. Like a wounded tiger, I refused to plead guilty to this new charge of conspiracy. All of our assigned lawyers begged us to plead guilty, “to get it over with.” Keegan was permitted to visit each cell to urge me and the other defendants to plead guilty – all in the name of justice. That I convinced 26 of our men not to plead guilty is a feather in my cap. However, I don’t think that many of them remembered that after their release in 1945 – to live as free men with their families, without a criminal record.

The prosecutors, now fearing that they would have to go to trial, hated me more than ever. My punishment began immediately, as I was illegally segregated from my alleged “co-conspirators.” I sat in a cage upstairs, all by myself, while a desperate Keegan, who had also been indicted, spread his poisonous views among the others. However, this arrangement did not work as well as planned, for an old friend and comrade managed to overcome this obstacle. Through him I received news of developments within our ranks, and was able to funnel advice back. Soon thereafter, I was transferred to the Tombs prison [in lower Manhattan]. Before leaving, however, I once again advised our men to plead “not guilty.” Keegan had never expected such a stand to be taken. Frantic in his efforts, our men responded that if he [Keegan] were to plead guilty first, then they, too, would consider such a plea – to which he responded by emphatically stating that he was no “Nazi,” and, therefore, was not “guilty.” Our men only laughed after hearing this “true confession.” And, since he could not deliver the guilty pleas [that the prosecutors wanted], Keegen was soon forced to defend himself in court, along with the rest of us.

Upon my arrival at the Tombs prison, I should like to mention, I was put in a cell that had been occupied by a man who had just been transferred to Sing Sing prison for execution. Likewise, when I was later sent to the Milan federal penitentiary in Michigan, I was put in a cell that had been occupied that very same morning by a Mr. Stephan, a candidate for execution. (Mr. Stephan, a restaurant owner from Detroit, had been entrapped by the FBI for harboring a phony German prisoner of war, who approached him seeking help after claiming to have escaped from a Canadian prison camp. Why they decided to persecute such a man, I have no idea. Anyway, we were able to watch

his gallows being constructed in the prison courtyard.) And, again, upon transfer to Washington, D.C., to face sedition charges, the former Bund members who were charged in that case were placed in the cells previously occupied by the German “submarine saboteurs” prior to their execution. Of course, all this was done for effect.

Anyway, returning to the trial in New York: when the proceedings began I was transferred back to the jail where the rest of the defendants were interned. It wasn’t long before we had a run-in with the “Brown Gang” – Jewish extortionists from the film industry in Los Angeles. At the time, these criminals were working in the [prison] doctor’s office, and they would assault some of our older comrades when the doctor was conveniently out of sight. I was determined to put an end to this as soon as the opportunity presented itself. On a scheduled visit to the doctor’s office, I was questioned by one of those men, who repeatedly asked how many times I had contracted venereal diseases. I answered only once, “Never.” But he kept asking the same question, again and again, and each time he would get a little closer to me in an obvious attempt at intimidation. When he got so close that I felt threatened, I shoved him with one mighty push. He ended up sprawled on the other side of the floor. The questioning was over, and thereafter the others in our group were treated correctly.

Each day, before we left for court, and again upon our return to prison, we were strip-searched for hidden contraband in front of the cell of Mr. Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, the Jewish boss of “Murder, Incorporated,” who found the proceedings quite amusing. These degrading gyrations, one would have to see to believe. Poor Mr. Fitting, our Lutheran pastor, died a thousand deaths each time. (From Trenton, N.J., he was one of our older comrades. His own Synod had dismissed him because he had said from the pulpit that he did not believe in Bruno Hauptmann’s guilt.) Upon arrival in the court, we, the defendants, were seated in a corner opposite to the jury, while our assigned attorneys sat in front of Judge [Alvin] Barksdale. We were thus unable to communicate with our lawyers during the trial, in violation of our Constitutional rights. The media, of course, had declared us guilty right from the outset, and the media climate made our legal defense all the more hopeless. The outcome was a foregone conclusion. We were found guilty and sentenced to five years imprisonment. / 9

Shortly thereafter, my comrades were transferred to various Federal penitentiaries where they would serve out their sentences, while I resolved to remain behind in New York until the appeal process began to move. A short time later I was informed that comrade Gustav Elmer, the former Treasurer of the Bund, had suffered a nervous breakdown and would soon be sent to a place in Missouri for the “criminally insane.” I never heard of him again, but I often wondered about the “criminally insane” who were persecuting us. Here I would like to mention that two of our elderly [co-defendants] had suffered heart attacks when the FBI kicked in their front doors. And, comrade Froboese was found crushed to death under a railroad car while on his way to the Grand Jury hearing in New York. (After reading of Froboese’s death, I sent a wreath with the inscription “Your Comrades from the East.” It was regarded as a criminal act because I had robbed my little girl’s piggy bank to pay for this gesture!)

The appeal [process] progressed more slowly than I had figured and, feeling uneasy, I decided to start doing some work in the prison. Some inmates were busy at the time trying to build a new tiled shower. When I told the guard on duty that I could make a fine job of it, he was delighted. The reputation I gained from that job would eventually precede me to the federal penitentiary in Milan, where they were planning to lay a red quarry floor over the old broken Terrazzo floor in the big mess hall. Most of the other Bundists were transferred to the federal penitentiary in Sandstone, Minnesota, where they were put to work in a sandstone quarry, often working under the harsh conditions of sub-zero winter temperatures. I would meet most of these comrades again on Ellis Island in December 1946 – this time fighting deportation, as we had, by then, been illegally stripped of our citizenship. (As a matter of historical record, our appeal was later decided in our favor by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1945, when that tribunal admitted that no evidence had been brought against us during the trial in New York.)

Along with another fellow, I was transferred by auto to the Milan penitentiary. On the way, we twice had to sleep in city jails, all the time shackled to two marshals. How dirty those city jails were has been engraved in my mind ever since. The administration of the Milan penitentiary is also unforgettable. The 33 German Americans held there were segregated from the other prisoners and were searched for contraband six times a day. Never was anyone in our group permitted recreation. I soon asked the warden for an interview to discuss the conditions of our incarceration. When we met to talk, he had the gall to tell me that these measures were being taken for our safety! I told him that I found it rather ironic that while the prosecution in New York had argued that we were ordinary criminals, prison officials should treat us as political prisoners.

Upon arrival at the Milan penitentiary, I was put to work on the mess hall tile project. However, they refused to give us the right tools to do a proper job. With a hand glass cutter and a regular pair of pliers, we cut the one-inch square tiles. When the time came to clean the cement stains off the finished part of the floor, I asked for a gallon of muriatic acid, but that was not provided because, we were told, we “might drink the stuff.” So, on three different occasions I stood by as barrels of soap suds were poured over the tiled floor, which the workers would then scrub without effect. Stupidity like that could drive a man crazy. Paul, the best worker in our crew, was sent to the “hole” for 21 days for refusing to work on just such an occasion. When he returned, looking like an emaciated ghost, he told me that I should be courageous like him. “Paul,” I said in response, “when that day arrives, consider me as being crazy, too!” Sometimes one has to learn to say “Yes, Sir!” and “No, Sir!” to the most undeserving clowns.

When the job was about four-fifths finished, the Portland cement that was used to stick the tiles to the floor ran out. I was subsequently called in to the warden’s office and charged with “sabotage” for using too much cement during wartime. Faced with this ludicrous accusation, I could only counter with the question of whether or not they were satisfied with the quality of the work done so far. The prison staff was of the opinion that my question was irrelevant to the issue at hand. They were judging me by their hatred, and once again I felt a deep pain in my stomach. I threatened to write a letter to Mr. Bennet in Washington, D.C., who was then head of the federal prison system. I believe I made my best propaganda speech ever. Anyway, the warden let me go back to work without punishment.

As Christmas 1943 neared, prison discipline seemed to relax somewhat. We were even granted permission to hold a Christmas party on the third floor of our segregated facility. Carried away by the spirit of the occasion, an artist painted a Christmas tree on a bedsheet, and cocoa and cookies were smuggled from the kitchen, where many of our group worked, including our slightly touched butcher. He had sung German songs at Liverpool harbor, England, while working on board an American ship, prior to the US officially entering the war. He was therefore accused of being a “spy conspirator.”

My health continued to deteriorate in the Milan prison. I doubt that I had more than half the blood a grown man of my size should have had. On occasion my knees would swell up like balloons. Once, I was kept in the infirmary for several days with warm electric pads applied. I worried that after my release I would not be able to support my family because I might be crippled. Yet prison officials still refused to supply us with knee protectors for our use while working on the floor. One could feel the hate directed against us. When two marshals arrived from Washington, D.C., on Jan. 4, 1944, to put me on a bus for Toledo, Ohio, I had a feeling of great relief. No matter what lay in store as a result of the “sedition” indictment, at least I was getting out from under such hateful bondage. However, upon arrival in Toledo, late in the afternoon, things suddenly turned sour again.

After chasing three sailors from a bench in the middle of a large waiting hall filled with thousands of commuters, the two marshals took out a long, heavy chain from a satchel they were carrying, and began winding it around my leg. When they finished their work, the two men went around telling everyone about the big “Nazi” they had captured. Before long, people began to crowd around, pressing steadily closer. I fainted from lack of air, falling from the bench onto the floor. Regaining consciousness after smelling salts were applied, I awoke to the smiling faces of Red Cross nurses, who gave me a drink of water. A group of soldiers kept the crowd away, and even the bragging marshals looked a little stunned after what they had done. However, that did not keep them from literally dragging me across several open tracks on to our train for Washington. Once on board, they again used their heavy chain to fasten me on a bed. I fell asleep in sheer exhaustion, and only woke up after arriving at Union Station in Washington, D.C.

My new domicile was known as the Burgh. Segregated again, each man in a single cell, life in many respects was better than anywhere I had been before. Here I was able to buy a quart of milk each morning, which I slowly sipped all day long. I used the toilet bowl as an “icebox,” flushing it often to keep the water as cool as possible. I read frequently during my stay in the Burgh, though the selection of books in the prison library at first left a lot to be desired. However, when Wilhelm Kunze took charge, things changed. By the time I left, three years later, more than 3,200 new books had been registered.

Several weeks of loneliness and contemplation passed. Then, one morning at about 11 o’clock, I was suddenly confronted by the whole prison staff standing in front of my cell. In a faked, jesting “scare,” I threw up my hands, claiming that I was innocent of any wrongdoing. As it turned out, though, all they wanted to know was whether or not I would be willing to work. They had also heard of what I could do with tiles. At first, the promise of better living quarters did not move me. However, after they promised to secure the right tools (“Just say what you need, and we’ll get it”), I acquiesced. They then took me to where they wanted me to work.

In wartime Washington, the Roosevelt Administration wanted to keep the “Citadel of Democracy” clean of pimps and bums. So, each weekend, about a hundred or so derelicts were arrested and then dumped into the Burgh on Monday. Receiving so many new inmates on one day, the officials in charge soon found that their facilities for washing, clothing and delousing these transient guests were inadequate. The warden had decided, therefore, to construct more bath stalls. That was easier said than done, however. Some black prisoners claimed they could do the work, but it was not long before the warden cried out: “Stop, you’re destroying the jailhouse!” When I saw the mess, I made a new demand right then and there: to fire all of those so-called workers, and give me two helpers who were willing to listen and learn. “Accepted!,” was the immediate response from the maintenance boss. I then made a list of the tools I would require for the job. To my surprise, everything I asked for was there the next morning.

That afternoon, I was moved to new quarters. All workers were housed in this area, and lights would stay on there until 11 o’clock at night. Soon, all of the indicted members of the Bund were in this block, and were working on one job or the other. Hermann Schwinn, our comrade from Los Angeles, worked in the front office. Throughout the war years, he would telephone for supplies all over Washington. So, through him we could also reach our attorneys, if necessary. Mr. [Hans] Diebel, former owner of the Aryan Book Store in Los Angeles, also worked there. It was also there that I met Mr. [Robert] Noble and his associate, Mr. [Ellis] Jones, also from California, as well as Mr. [William Dudley] Pelley, the former “Silver Shirt” leader. Noble had been leader of the Ham and Eggs California Pension Plan ballot initiative, and leader of an anti-war organization. / 10 All these people were co-defendants in the [1944] Sedition trial, but they had also been sentenced in previous cases brought under the Roosevelt administration. Noble had the job of cleaning the derelicts and putting their clothes in the “gas oven” for delousing. He would also sort out those among the new inmates those to be sent to the hospital. After those not destined for the hospital had “dried out,” they were put to work in the prison kitchen, where they generally made a mess of otherwise good food. I often wondered how those in charge were able to feed so many with such incompetent help. They once nearly poisoned almost 300 of us with a Sunday dinner. On that occasion, I had given my own serving of meat to Mr. [George Sylvester] Viereck, who didn’t object to the foul smell. He returned to our dormitory from the hospital three weeks later.

Viereck had been jailed simply because he had some good words to say about Hitler and the Germans in general. Once, after proclaiming “Hitler is eternal and, therefore, will never die,” he was chained to wild blacks on his way to and from Court. One funny thing about Viereck: he claimed that [the] Hitler [regime] burned all 20 of his pornographic novels. When I first met George Sylvester Viereck, I often felt like choking him. However, living together in the same cell block for almost three years, I grew to feel sorry for that pathetic figure. He required all kinds of decorations and cosmetics in his cell, and we supplied him with the things he needed to feel happy. Every so often his cell was raided and stripped of his prized possessions. We would then proceed to slowly replace every item, piece by piece.

Unfortunately, I do not have time to talk about all the people I came to know during my stay in the Burgh. I should like to mention, however, that it was a great privilege and honor to be able to meet and shake hands with Ezra Pound, America’s great poet. Talking with him, you could just sense the power of his intellect. What a difference there is in Man! Some stand so tall, they can never be mowed down. No wonder he was quickly removed and put in a facility for “crazy” people. I can tell you, in all honesty, that I never met a more sane and courageous man.

On the other hand, there was the Baptist minister who visited us every Wednesday in a futile attempt to save our souls. After Roosevelt had passed away, I asked him whether he thought the President had gone to heaven. “Yes, my son,” he replied, “Roosevelt was not only the greatest president America ever had, but a saint-like person who certainly is in heaven now.” “My dear pastor,” I replied, “Didn’t he cause me and my people enough suffering on Earth? Now you want me to live for all eternity in a place where he, no doubt, rules supreme once again! No thank you!” The minster left, saying that I was “a hopeless case,” and we never talked again.

Returning to the subject of prison work, after my first day on the job, the maintenance chief told the other officers in charge of work details that I was his boy and no one had the right to remove me from my assigned projects. As a result, I was able to complete most of the emergency construction work before the trial started. That was fortunate, because once the trial started [April 17, 1944], we wasted so much time in Judge Eicher’s court, that I worked only on Saturdays. Working in my trade gave me a great deal of satisfaction and pride. Mr. Jones, on the other hand, often criticized me for doing “a hundred thousand dollar job for the bastards,” as he called them. He was 72 years old at the time, and was never forced to do any work. The administration also appreciated my work, and I seldom had any hassle with prison officials, save the doctor. Every now and then, he would take me off my diet, which consisted of an extra six ounces of milk. I still have the letter of protest I wrote to him late in October 1946, shortly before Mr. Schwinn and I were transferred to Ellis Island for deportation.

After the death of Judge [Edward] Eicher [on Nov. 29] in 1944, after only eight months of hearings, the trial was suspended indefinitely. By this time, I had finished most of the tile work on the new shower stalls, and had taught myself how to weld metal with a new-fangled electric welding machine, which had just been idly standing in the maintenance shop because no one knew how to use it. I read the manuals several times before I put it into action, and was soon busy at work using my new-found skills.

Blacks and whites were segregated in the Burgh. Never did I have to fix a bed in the white section. Fixing beds in the black section, on the other hand, was a regular chore, as the Africans would jump up and down on their beds, to the beat of that jungle music which now has become such an integral part of “American” culture. My boss would say, “Augie, another bed needs repair!” He would then send me to pick it up with instructions that the wild ones carry the fruits of their mischief down to the shop. Once in the shop, I would then weld steel strips in a weaved pattern onto the iron bed frame. Whenever I finished work on one, my boss often exclaimed, “The bastards will never break that again!” And in the three years I spent in jail in Washington, they never did.

Another job worth mentioning concerns the execution of six million cockroaches in the old wooden bread racks in the kitchen. Our bread was baked in Loudoun prison, Virgina, and it tasted like sawdust. In fact, on one occasion one of our more flamboyant lawyers, Mr. Laughlin, literally smashed a dried-out sandwich made with that bread while he pleaded for better nourishment for those of us who were incarcerated. The cockroaches however, liked it very much, and hosts of them ate freely of it before it was served to the inmates. Cockroaches were so ever-present in the kitchen that they often swam in our soups and stews – and often still alive! One day, my boss said to me, “Augie, we have to do something about these pests.” I suggested that we replace the wooden shelves with steel ones. He agreed. So we proceeded to manufacture the steel shelves in sections. Shortly after completion of that task, the afternoon of the great massacre arrived. All of us, blacks and whites, illiterates, pimps and derelicts alike, were united in one mighty effort. With acetylene torch aflame in hand – and as others busied themselves pounding the rotten woodwork and sweeping the pests toward the center of the kitchen floor with large brooms – I systematically incinerated the entire population of six million. However, the stench was so great that everyone who came for supper that evening lost his appetite.

Concerning the trial itself, the sedition charges brought against the defendants were, of course, ludicrous. Part of the evidence marshaled against me was an article I had written prior to America’s entry into the war, warning that Roosevelt could not be trusted when he promised not to send American boys overseas, since in reality, he was already at war with Germany. In that article, I also predicted that should Germany lose the war, the winner would not be America, but Bolshevism. Communist prosecutor John Rogge read my article to the jury, word by word, emphasizing that ten years hard labor in prison would be sufficient punishment for the author of this lying diatribe. History, however, has proven me correct. Also, my one dollar contribution to the 1938 Winter Relief Fund in Germany, given by the Bund, reared itself again as evidence of my disloyalty to America. That had also been one of the accusations leveled against me in the New York trial. To that absurd charge, I countered that I was ashamed of my small contribution to such a worthy cause, and that it was totally unnecessary to keep reminding me of it.

More unbelievable still was the host of witnesses who were brought in to testify against us. One worth mentioning is an alleged Mormon cleric [missionary?] who testified that he and a fellow Mormon had been driven out of Hitler’s Germany due to religious persecution. It suddenly occurred to me that his story sounded awfully familiar. Paxman, the FBI agent who had never tired of harassing me in New Jersey prior to the war, often claimed that he and his partner had likewise fled persecution in Germany, luckily escaping to Switzerland. I quickly put two and two together. In the minutes [transcript] of the trial [proceedings], one can read how much potato salad our lawyers made of this agent [discrediting him], masquerading as a Mormon cleric. No doubt, Mr. Paxman would also have appeared to testify, had he not died in a plane crash. Be that as it may, one has to ask: just what do colorful, unsubstantiated stories of religious persecution in Germany have to do with sedition in America?

Another witness for the prosecution was Mr. [William] Luedtke, former National Secretary of the Bund, who turned traitor and became a parrot for the eternally “Chosen.” Protected by the Judge, our lawyers in Washington were unable to topple his false testimony. During the earlier Bund trial in New York, that had still been possible.

The prosecution’s star witness, however, was Dr. Robert Kempner, a Jewish refugee from Germany, who was called to testify regarding the meaning of German folk songs popular during the National Socialist era. This lying Jew shall be forever ingrained in my memory. Dr. Kempner’s special skills, however, could not be properly put to use in America. Later in the “war crimes” trials at Nuremberg and throughout Germany, he helped the prosecution with “confessions” obtained through torture and mutilation of German prisoners of war. And, as unbelievable as this may sound, the West German government recently awarded this character with its highest decoration, the “Cross of Honor,” to commemorate his contribution to the “new” Germany. (Simon Wiesenthal has also been so “honored” by the West German government.) When a former friend of mine, presently active in German American circles, also received this award through the German Consulate in New York, I told him outright: “If you want to be my friend and comrade, go back to New York and throw that piece of worthless junk metal in their face.”

Details of the trial can be gleaned from the book written by Lawrence Dennis [A Trial on Trial: The Great Sedition Trial of 1944], and the memoir of [co-defendant] Rev. David Baxter. / 11 The impression given by both authors is if the trial had continued to a conclusion, the jury would have acquitted the defendants. There is no question but that the jury would have freed some of us, but I strongly doubt whether they would have acquitted the hardcore National Socialists. Let us not forget that they are still persecuting so-called “Nazi war criminals” 40 odd years after the war, deporting elderly American citizens to Europe and Israel to face show trials.

Concerning Judge Eicher: he was a man of little character. Everyone in court knew why he had been appointed to head this trial. Even Attorney General [Francis] Biddle had protested to Roosevelt that there was no law under which to indict the defendants. Of course, that was the least of Roosevelt’s concerns. Throughout the trial, the defense attorneys would commonly refer to him as a SOB, as he frequently overturned their motions. However, on the morning it was announced that he had passed away during the night, all 20 or so lawyers stood in praise of the judge, with eulogies that lasted for hours. Suddenly Judge Eicher the SOB had become a “saint.” I felt like crawling under a bench and remaining there until this display of Anglo-Saxon hypocrisy was over.

Many things happened during the course of the two years we awaited a new trial. We heard from the Reverend Baxter that [O. John] Rogge, the Red prosecutor, had left for devastated Germany with an army of assorted liberals and Bolsheviks. History records the vile acts they committed against the German people. Few are aware, however, of their frantic efforts to connect us, the former members of the Bund, with the National Socialist government in Germany, by sifting high and low through official German documents. And after nearly two years of conducting their search, they still could not find any such evidence. Our only connection to Germany had been our common ideals. That was something the prosecution simply could not accept. Even today, I admire Adolf Hitler and retain my National Socialist conviction.

It is this conviction which sustained me through the hardships of my life. In short, I never had any trouble knowing where I stood. Others were less certain in their position. For instance, at the war’s end, on hearing of [what is now called] “The Holocaust,” Mr. Pelley said to me: “Augie, I too, now believe it was necessary to go to war against Germany.” “Mr. Pelley,” I replied, “Do you think that I would be capable of such atrocities?” “Oh, No,” he said, “you could never do such horrible things.” “Well,,” I responded, “you are accusing my brothers and sisters.” I abruptly left him, mouth wide open. We avoided each other from that day on.

Anyway, a new trial never materialized. Then, suddenly, on December 6, 1946, Hermann Schwinn and I were removed from the Burgh, en route to Ellis Island. I did not even have a chance to say good-bye to my boss and co-workers in maintenance. The funny thing was, we were to be transferred without handcuffs. “What, no handcuffs!,” I said to Hermann. “Isn’t such freedom suspicious?” So, with a feeling of mistrust, we awaited the train for New York. Before boarding, I decided to buy a cigar for Hermann, when a perfect stranger approached me and put a piece of paper in my hand. It was a short note from Kunze’s lawyer, Mr. [Bateman] Ennis. (Before leaving Washington, Mr. Ennis had promised to open up my citizenship case in New Jersey as soon as it appeared that the witch-hunters had stopped all criminal indictments against me.) Anyhow, the note indicated that the powers that be were intent on sending us, not to Ellis Island, but to Germany via a ship waiting in New York harbor. Mr. Ennis had caught wind of this scheme through a man in the Immigration Department, and had instructed his associate in New York, a Mr. Singer, to a file a writ of habeas corpus on our behalf. This action proved effective and, after a long delay in Hoboken, N.J., we were transferred to Ellis Island.

Mr. Ennis, true to his word, immediately set to work to regain my lost citizenship, and the first hearing took place before Judge Smith in Newark, N.J., on January 17, 1947. My presence was not required, so I remained on Ellis Island. I must say that this was truly fortunate, as a crowd of several thousand showed up in protest, incited by the radio broadcasts of Walter Winchell. Most probably they would have tried to trample me to death. They certainly did ruin the health and career of Frederick Pearse, the Jewish lawyer who had been asked by Mr. Ennis to represent me in New Jersey. With the crowd screaming obscenities, gesticulating wildly, and throwing money in his face, the poor man was considerably shaken. This unruly mob of Zionist hecklers had broken through the police barricades, and were so noisy and disruptive in court that no one could follow the proceedings – not even the judge. Of course, the outcome of this show trial – in which people were brought in to testify against me whose only knowledge of me and the case was what they had read in newspapers and heard on the radio – was a foregone conclusion. However, determined to fight this fight through to the bitter end, I decided to appeal, and the case next went before the Appellate Court in Philadelphia, and then before the Supreme Court, where a decision was handed down in my favor in 1949.

Mr. Schwinn, on the other hand, upon release from the Burgh, no longer had the spirit to continue the fight in court, and he secured a visa for emigration to Argentina. I never heard of Mr. Schwinn again. Later, I too would apply for and receive a similar visa when it appeared that all was hopeless. On Ellis Island, the Lady in the harbor had turned her back on the Germans, as thousands were deported, while “survivors” of the “gas ovens” were welcomed with open arms. Working maintenance once again, I had many occasions to converse with the newcomers. They were often glad to talk to someone in German and, I swear, no one ever spoke of seeing their babies, or their grandmothers, or anyone for that matter, burned in “gas ovens.” On one occasion, two Polish Jews even confidentially showed me their money belts stuffed with crisp new $20 bills, and asked me how they should invest their money. Poor persecuted ones – up from the smokestacks in Europe to land feet first in America. More unbelievable still, and far more disgusting, a German-American helping hand organization out of New York, called Deutsche Gesellschaft, came to the Island twice weekly to help these incoming Jews, while ignoring their own flesh and blood pining away on Army cots. I saved many a life by moving those cots when cracks developed in the old plaster ceiling overhead, which sent large chunks of plaster crashing to the concrete floor below.

Time does not permit me to discuss in detail my stay on the Island. However, I would like to mention a couple of episodes that may be of interest. The first concerns Gerhart Eisler, the Communist activist and spy, who was transferred to Ellis Island and put in our sleeping quarters. Soon thereafter, the [New York] Journal American [newspaper] published an article reporting that “Nazis” and Communists, imprisoned together [at Ellis Island], get along most harmoniously. This article infuriated me to the point where I could not sleep that night. So, I devised a plan to counter this propaganda. The following morning, after breakfast, I approached a guard on duty and asked him if he could keep a secret. When he said he could, I proceeded to tell him that the “Nazis” did not like the idea of a Communist being brought into their midst, and that I had talked them [“Nazis”] out of doing any harm to him [Eisler], at least for the time being. A few minutes later, I was called into Mr. Forman’s office, where I was asked to reveal the names of those who wished to harm Roosevelt’s protege. “Mr. Forman,” I replied, “if I told you that, my life would be in jeopardy, too.” That afternoon, the Journal American came out with the headline story that Mr. Eisler was being taken out of reach of the “Nazis” for his own safety. Later, he “escaped,” boarding a Polish ship bound for Communist East Germany, where he became a high-ranking official. It goes without saying, of course, that no one could escape from Ellis Island without inside help. Anyway, that nonsense about “Nazis” and Communists being cut from the same bolt of cloth was dispensed with.

Another episode concerns a visit to the island during June 1948 by three men: Senator [William] Langer, Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, a Mr. Fox, representing the Justice Department, and a Mr. Shoemaker, representing the Department of Immigration and Naturalization. Allegedly, they came to pass final judgment on those remaining as prisoners on the Island – that is, to recommend whether they should be set free or deported. I was the first to be called before this board. In my opening statement, I frankly asserted that I considered these proceedings a farce, for no one here was free to pass a favorable judgment on the former members of the Bund without putting his career in serious jeopardy. At this point, Mr. Shoemaker literally flew into a rage, exclaiming that he would willingly “shoot me on sight” should there be another war with Germany. He then proceeded to question me in a most idiotic fashion concerning just such a possibility.

Frustrated with my answers and agitated to the limit, Mr. Shoemaker eventually got up and left the room. I shortly followed suit, declaring that I certainly could not expect justice in this room, when one member of the board wants to “shoot me on sight.” However, Senator Langer came running after me and said, like a well-meaning father: “Augie, Come back and sit down and we will discuss this matter more serenely. I promise you.” You see, Senator Langer and I went back a way. He had visited me twice in jail while I was incarcerated in Washington, and he once brought my wife to see Attorney General [Tom C.] Clark, regarding the conditions of my imprisonment. On that auspicious occasion, the high priest of American justice actually asked her where I had stashed all the money I supposedly received from Hitler. Dumbfounded, she replied by simply telling him that if he still believed such “tired old fairy tales,” then she saw a dark future for America, indeed.

Anyway, following those Ellis Island hearings, 78 comrades were deported to West Germany, proving that those proceedings were purely for show. Later I learned that upon their arrival at the military camp in Germany to which they had been destined, a black sergeant called out my name three times during roll call. After receiving no answer, one comrade shouted out from the ranks that I “must have missed the boat,” which was quickly followed by a wave of laughter. I mention this here only to show that I was still targeted for illegal deportation, even though my citizenship case was still under review before the Supreme Court.

As I previously mentioned, I worked in maintenance during my stay on the Island. The maintenance work force – which was made up almost entirely of drunkards – was, to say the least, really something to behold. Consequently, Mr. Christiansen, the man in charge, greatly appreciated my work. On the day I left Ellis Island, which was July 18, 1948, he literally followed me down to the ferry, begging me to apply for a Civil Service job while on parole. Me? Work for the government? Can you imagine! Anyway, no sooner had I stepped off the ferry at Manhattan’s Battery Park that I was approached by two Treasury agents carrying bulging revolvers. They proceeded to insist that I sign a document stipulating that I owed the U.S. Treasury more than $800 in back taxes from 1939, including penalties and interest, relating to the seizure of Camp Nordland. I had not expected this encounter. It caught me completely off guard. So, I asked those two busy men if I could sit on a park bench nearby and collect my thoughts. It must have taken me a good ten minutes before I could think clearly again. I decided to sign the document. After all, I reasoned, what’s an additional $800 on top of all the other debts I had accrued while working as a slave-laborer for more than six years! That done, the agents vanished as quickly as they had appeared.

While on parole, I was to report twice a week, in person, to Mr. Forman’s office on the Island. I quickly realized, however, that I could not possibly hold a job for long under such parole conditions. So, and as hard as this may be to believe, after just two weeks of “freedom,” I asked Mr. Forman if he could arrange for me to return to the Island. He immediately agreed that I would now only have to telephone [rather than report in person]. That routine went on for months, and then it, too, came to an end. I should also mention that upon being released on parole, I was not given a “green card,” which all legal aliens are required to carry at all times. Here, again, I was forced to rely on my wits. So, I immediately sent a registered letter to the Department of Immigration and Naturalization, claiming that I must have “lost” it. Within a few days, I received my “new” card, which I still carry after all these years.

Anyway, there was plenty of work on the outside, and I had little difficulty finding employment. However, my burden of debt was so great that often I could not send the IRS the amount they demanded as payment toward its $800 claim against me. The agency would then approach my boss to have my pay attached [garnished] directly. And every time that happened, I was let go. No one wants to be involved in messy government affairs. After several such episodes, I decided to make an appointment with the head of the IRS office in Newark. There I was informed that everything happening to me was my own fault. I tried, in vain, to explain my situation. However, nothing I said made even the slightest impression on him. I shouldn’t have taken that day off from work.

Meanwhile, the day finally arrived when the Supreme Court was to hear my citizenship case. Mr. Ennis had called me from Washington to tell me: “Come on down, Augie, and let them see you without those horns the Zionists have painted on you.” So, I flew down for the 1948 October Term. Sitting before that body in awe, I spotted the face of Justice [Robert] Jackson, who had recently returned from his lynchings in West Germany. / 12 I could not take my eyes off that evil man. Simple justice would have demanded that he remove himself from the case due to prejudice, not to mention malice. But, then again, justice is really not a major concern of the American legal system. And even though the high court decided five-four in my favor on January 17, 1949, a week or so later, Justice [Felix] Frankfurter, in an unprecedented move, reversed his decision. And so, the case was now to be re-opened in Newark.

Back in New Jersey, the government marshaled 29 witnesses to testify against me. My key witnesses, on the other hand, all former comrades, could not to be found. And considering what my family and I had been through, I could not blame them. Only Dr. Bergmeier, and my former landlord in Union City, showed up on my behalf. The outcome, as in every other proceeding, was a foregone conclusion. / 13 Judge [Arthur] Lederle had been transferred to Newark by the “hidden hand” just prior to my trial. During the war years, with the help of Bund traitor Willie Luedtke, he was used to denaturalize German-Americans in principal US cities. The outright lies this judge told in court about me personally knew no limit. When I attempted on one occasion to tell of the illegal acts that had been perpetrated against me during the course of years, he pounded his hammer furiously on his desk, exclaiming that things like that don’t happen in America, adding that I was only a “Nazi propagandist.” He then threatened me with “Contempt of Court” should I continue to try to defend myself in that manner. I would also like to mention that Mr. [Edward] McDonald, my assigned New York lawyer, was absolutely no help at all. Having just become a U.S. Commissioner, he knew where his bread was buttered.

Anyway, with the verdict in, a second appeal was drafted to be brought before the Supreme Court. Former comrades came to my home and begged me to give up the fight, thereby easing everyone else’s difficulties, or so they thought. Again, I felt no animosity toward those men who, like me, had been incarcerated for more than six years. Anyway, the appeal was denied and, in April 1951, I received an order for deportation. All my legal options had been exhausted. Then, at this critical moment, Pastor Riedel phoned, offering to go to Washington to ask for an extension on the deportation order. All he requested was $35 to cover travel expenses.