Clash of Forces in North Africa: Bagnold’s Bluff

The Little-Known Figure Behind Britain’s Daring Long Range Desert Patrols

Trevor J. Constable

Specialist military units of the commando type enjoyed wide vogue during the Second World War, and what little military glamor shone through the conflict was confined almost exclusively to these private armies. They were the stuff of which legends are made. Bold leaders harassing armies with mosquito forces naturally became headline heroes in a war of otherwise inhuman mass effects. Ord Wingate and his Chindits in Burma; Evans Carlson and his Marine Raiders in the Pacific; Mountbatten’s commandos; “Phantom Major” David Stirling and his Special Air Services force in North Africa; and on the other side the unforgettable Otto Skorzeny. The list of famous names is lengthy, and even today they evoke memories of high adventure and piracy. Missing from among them is the brilliant progenitor of all these private armies of modern times, the soldier-scientist who conceived and built the first and most successful of them all — Ralph Bagnold.

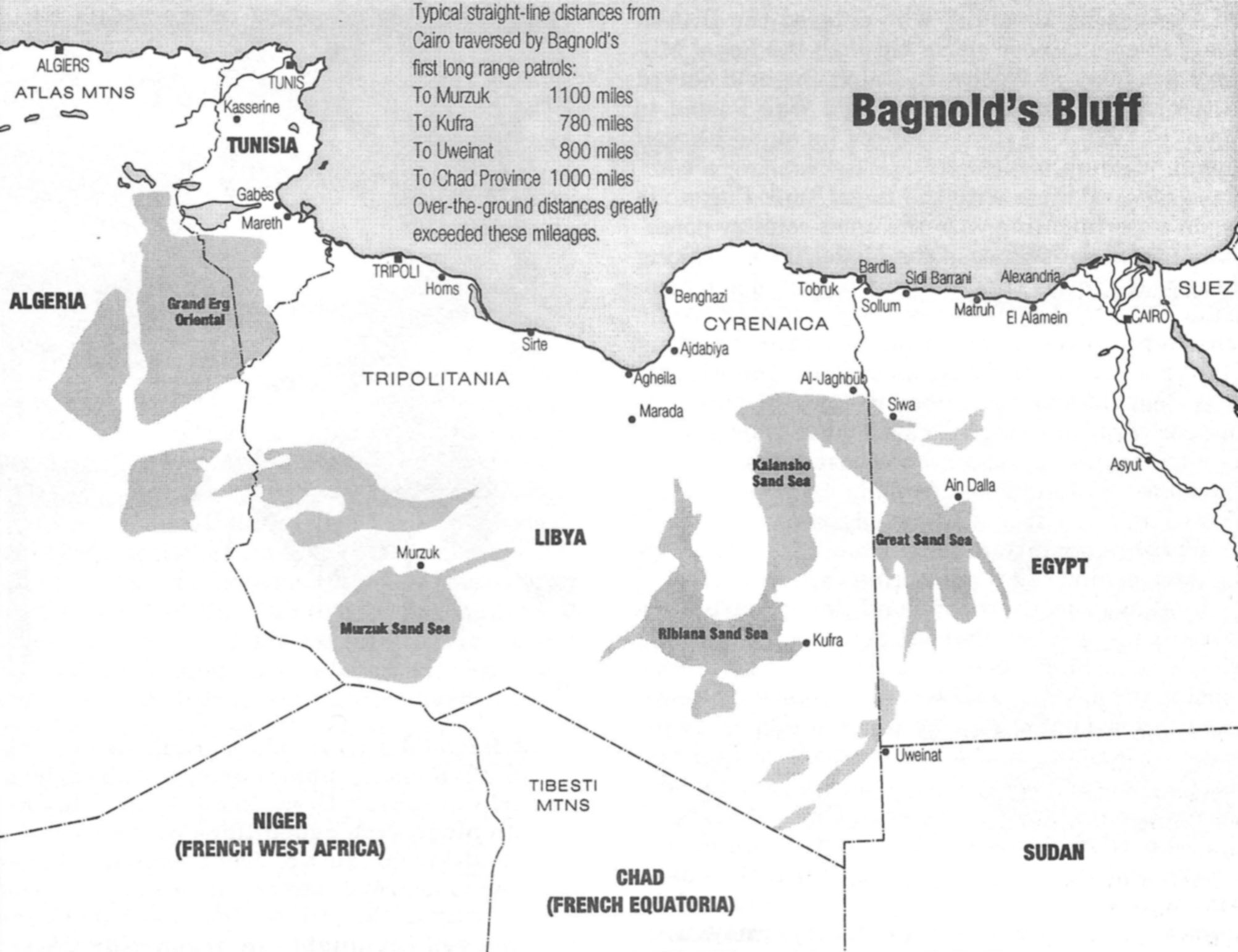

This tough-minded yet visionary Englishman played a decisive part in bringing the Allies through the serious crisis precipitated by Italy’s entry into the war. The loss of the entire Middle East was an imminent possibility. The dramatic, unexpected flanking diversion provided by Bagnold’s long range patrols — operating across the mountainous, scorching dunes in the interior of Egypt and Libya — tipped the strategic balance against the Axis. Military units had never penetrated these vast, unmapped wastes before, and First World War patrols had gone no farther than their fringe, where they recoiled from the impassable barrier of the giant dunes. Formal military thinking on North African topography routinely took its cue from this experience. The dunes were deemed to be impassable. The success Bagnold achieved in the teeth of these and other orthodox military conceptions opened many minds in the Allied high command, paving the way for numerous specialist units that followed.

The successful ones were built upon the foundation that Bagnold laid. He established the fundamentals of all small force success — planning, organization, the right equipment and communications, and a human element of exceptional quality. Adherence to these fundamentals could produce results out of all proportion to the size of the force, and with minimum casualties.

Today the ability of a small, highly-trained unit to penetrate to the heart of any country on earth has to be taken into account in protecting key leaders in the event of war. The Assassins of the twelfth century may have been the originators of this concept, but it was Ralph Bagnold who first showed in modern times what an élite and resolute small force could achieve in upsetting the strategy of armies. His achievement had its origin in a seemingly useless peacetime hobby that the English adventurer shared with a few friends. How he turned this hobby into a superior instrument of war, and was then hidden by the sheer bulk of the commando heroes who came later, is an example of historical caprice hardly rivalled in our time.

A professional soldier who entered the British Army as an engineer officer through the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, Ralph Bagnold served in the trenches in the First World War. Posted to Egypt in 1925 as a signals officer, he found himself among a group of kindred spirits sharing a combined officers” mess with the Royal Tank Corps. He began experimenting with the cross-country potentialities and endurance of the Model T Ford, taking these rugged early cars over rough ground and sand drifts where no car had previously ventured. While other officers spent their time at Gezira Sporting Club or enjoying the fleshpots of Cairo and Alexandria, Bagnold and his friends used their weekends and periods of local leave to make adventurous journeys in the desert. They probed eastwards to Sinai, Palestine and Jordan before made-up roads existed. Their leader by free acknowledgment, Bagnold’s enterprise, ingenuity and intelligence were the driving force behind these pioneering expeditions.

Unshaven in their informal desert garb hundreds of miles from civilization, Bagnold and his friends might have been considered highly unconventional by those who were content with more mundane recreations. They were intelligent, educated men indulging a common passion for the desert. Their numbers regularly included two young officers of the Royal Tank Corps, Guy Prendergast and Rupert Harding-Newman. Both were expert drivers, and Prendergast was also an enthusiastic airman at a time when flying was still a rare skill. Later they were destined to turn their journeys with Bagnold to good military account, although at the time the far-ranging journeys were merely a hobby.

Growing experience and confidence in his own logistics and specially-designed equipment turned Bagnold’s mind inevitably westwards to the frightening immensity of the Libyan Desert — the most arid region on earth. Roughly the size and shape of the whole Indian peninsula, its strange, wind-sculptured wastes, as rainless and dead as the moon, were largely unmapped and untrodden by man or beast since prehistoric times. Scorching, vast and silent, it presented an irresistible challenge. Intrigued by the prospect of conquering this desert of deserts, the English explorer began planning a new adventure.

Ralph Bagnold in a rare photograph taken by his friend Bill Kennedy Shaw during a 1932 exploration trip in Libya’s Great Sand Sea. During his private pioneering expeditions in the 1930s he learned the techniques of driving motor vehicles over the immense dunes of northern Africa, and of surviving in the pitiless desert – experience that proved invaluable in organizing desert patrols in 1940. With General Wavell’s backing, Bagnold’s daring patrols bluffed Italy’s Marshal Graziani into halting his drive to the Suez Canal. Wartime security suppressed the story of Bagnold’s history-changing achievement.

Could a small, self-financed party of six men, in three of the new Model A Ford cars penetrate the Libyan Desert as far or perhaps even farther than previous expeditions? The most recent exploration effort had been made by the millionaire Prince Kemal el Din, with a fleet of caterpillar trucks supported by supply trains of camels. Three Model A Fords seemed a puny expedition by comparison, but Bagnold felt that perhaps sheer size and resources were not the key to success. Might not a small party even succeed in crossing the enormous dune field of the Great Sand Sea? The width of that barrier was unknown, but it separated Egypt and Libya for five hundred miles from north to south. Prince Kemal el Din had judged the Great Sand Sea to be utterly impassable.

Despite this first-hand judgment by a contemporary explorer, Bagnold resolved in 1930 to try to conquer the dune barrier. His party included two British officials on leave from the Sudan civil service: Douglas Newbold, permanent head of the government, and Bill Kennedy Shaw, archaeologist and botanist. Both were Arabic scholars and experienced camel travellers, and both were burning with enthusiasm to explore the mysteries of the Libyan desert, legends of which abounded in ancient Egyptian records and in Arabic literature.

Bagnold’s planning and intuitive pathfinding succeeded. The bold little group discovered a single practicable route for light cars over range upon range of towering sand dunes. In their Model A Fords they covered some four thousand miles of unknown country before returning to Cairo in triumph. The Sand Sea route was retraced and mapped in detail shortly afterwards by Patrick Clayton, a tough, restless Irishman and expert cartographer employed by the Egyptian Desert Survey. Clayton’s grey hairs belied his drive, versatility and skill, qualities which earned him Bagnold’s respect and friendship.

After this successful penetration of Inner Libya, the Royal Geographical Society supported additional and still longer journeys. The primary exploration of the region was under way, but Bagnold’s interest had meanwhile been seized by the sands in a manner quite different from that of a conventional explorer. Fascinated by the extraordinary symmetry and geometrical regularity of the great dunes, he found that little was known to scientists about the formation and movement of these vast natural barriers. Retiring from the army, Bagnold turned scientist and embarked on laboratory research into sand movement. He wrote a treatise entitled “The Physics of Blown Sand,” which earned him election to the élite Royal Society of London — an almost unique distinction for a service officer with no academic qualifications beyond a Cambridge BA. He occupied himself with his scientific work in communications, hydraulics and fields connected with sand such as beach formation, until the outbreak of war in September 1939.

Major Bagnold was immediately recalled to the army. Ignoring his unique talents and specialized experience, the British Army bundled him aboard a troopship bound for Kenya — a country of which he knew nothing. The prospect of his years of desert experience going to waste was discouraging, but he could do no more than obey orders.

Fate intervened in the form of a mid-Mediterranean collision involving his troop ship. The vessel was so badly damaged that its passengers were disembarked at Port Said, where they would be required to wait at least a week for another ship, Seizing the chance to visit his many friends in the capital, Bagnold caught the first train to Cairo. A sharp-eyed reporter for the Egyptian Gazette spotted the greying major in Shepheard’s Hotel, the famous social mecca of British Army officers in those days. The reporter knew all about Bagnold’s prewar desert journeys and began putting two and two together. In his column “Day In, Day Out” he briefly reviewed Bagnold’s past achievements for his readers, and ended his column with the following observation:

Major Bagnold’s presence in Egypt at this time seems a reassuring indication that one of the cardinal errors of 1914-18 is not to be repeated. During that war, if a man had made a name for himself as an explorer of Egyptian deserts, he would almost certainly have been sent to Jamaica to report on the possibilities of increasing rum production, or else have been employed digging tunnels under the Messines Ridge. Nowadays, of course, everything is done much better.

Archibald Wavell (1883-1950), seen here as Commander-in-Chief Middle East. In the summer of 1940 he faced an Italian army in North Africa of more than 200,000 men that was poised to invade Egypt and seize the Suez Canal. Although he commanded much weaker forces, Wavell understood the power of strategic deception. Desert explorer Ralph Bagnold convinced him to pull an immense bluff, using long range patrols to attack remote Italian bases on the far southern flank. Italian commander Graziani “bought” the bluff and stalled his drive for the vital Canal. In the precious weeks of time won by Bagnold, Wavell built up his forces enough to smash the Italian army in eastern Libya, December 1940-February 1941.

Square peg Bagnold was, “of course,” on his way to a round hole in Kenya, true to the British Army tradition that the newspaperman had criticized. The course of the North African war was nevertheless to turn on what the reporter had written about Bagnold in the Egyptian Gazette. General Sir Archibald Wavell read the thumbnail sketch of Bagnold’s desert career in “Day In, Day Out,” and thus learned of the explorer’s presence in Egypt.

Although Wavell had no official status in the Middle East at that time, he was working behind the scenes on preparations for the inevitable expansion of the war in that theatre. The so-called “Phony War” was in progress in Europe after Germany’s conquest of Poland. The Battle of France still lay in the future. Italy was not yet in the war, and the open appointment of an eminent soldier like Wavell to command the Middle East might have been seized on by Mussolini as a provocation. General Wavell had therefore been sent out from England sub rosa, to plan for Italy’s entry into the war, or for a German thrust through the Balkans, or for both together. As if to emphasize his unofficial status, Wavell occupied a small office in the attic of the bulky HQ building of British Troops Egypt (BTE), the peacetime garrison force commanded by General Sir Henry Maitland “Jumbo” Wilson. Bagnold was completely unaware of all these arrangements when he began visiting old army friends.

The major’s first call was at the office in the same building of his old friend and contemporary, Colonel Micky Miller, then chief signal officer BTE. Miller’s face lit up as Bagnold appeared. “Just the man,” he said. “Wavell wants to see you. “Wavell?” said Bagnold, “what’s he doing here? I thought Jumbo Wilson was in command.” Miller put his fingers to his lips in a gesture of silence. “Hush,” he said, “Wavell isn’t supposed to be here. Jumbo’s our boss. Wavell has no authority to interfere. But he knows everything that goes on and remembers everything and everybody. He’s planning something big and he’s collecting people — people who know things. You’ll certainly be transferred here, Ralph. Come on. I’ll take you upstairs.”

As they climbed up to the attic Bagnold’s puzzlement grew at the modest quarters assigned to such a senior general. From Micky Miller came a quick aside as they reached Wavell’s office: “He’s got a glass eye, you know. So be careful to look at the good one.”

The interview was brief. The one very bright eye, set in a wrinkled, weather-beaten face, looked Bagnold over. The general spoke quietly.

One of Bagnold’s early Long Range Patrols is inspected in Cairo in 1940 before departure on operations across the desert and dunes of eastern Libya. At first made up largely of New Zealand volunteers, the patrols’ main tasks were to reconnoiter far west of the main fighting lines to report on enemy movements and dispositions. Later known as the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), and greatly expanded, the patrols were active throughout the North African war. The LRDG was organized in a dozen truck-borne patrols, with ten trucks to a patrol and some six men per truck. Its tactics and administration were fluid. More than 50 of its members were decorated for gallantry, and only 16 were killed. “Considering its size,” concluded “The Historical Encyclopedia of World War II” (1989), “it [the LRDG] exercised a wholly disproportionate influence on the desert war.”

“Good morning Bagnold. I know about you. Been posted to Kenya. Know anything about that country?”

“No sir.”

“Be more useful here wouldn’t you?”

“Yes sir.”

“Right. That’s all for now.”

As Bagnold walked out he pondered on the inscrutability of that remarkable face. Was it grim, or smiling at the prospect of some half-formed plan? Even in those brief moments there was an impression of quiet power about Wavell.

Two days later a cable from London transferred Bagnold to Egypt, and was followed by a local posting to a signal unit of Major General Hobart’s Armored Division at Matruh, on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. He was back in the desert again. Cancellation of his Kenyan assignment was like a redemption, but in later years he would marvel at the delicate pinions of maritime collision and newspaperman’s acumen on which his destiny had turned.

Within a few weeks, his geographically broader outlook grasped the alarming weaknesses of the defense situation should the huge Italian armies in Libya and Ethiopia attack the Nile states of Egypt and the Sudan. The one British armored division in North Africa, newly formed and crucially short of transport, would be put to its limit to defend the 60 mile-wide “Western Desert” — the maneuverable coastal strip between the Mediterranean and the northern edge of the great sands. A major Italian thrust to seize the Nile Delta was certain to come from Italian Libya eastwards in the event of hostilities. Five hundred miles to the south, the Italians were known to maintain a garrison at ‘Uweinat on the Sudan border, well beyond the southern limit of the Sand Sea. Bagnold knew this country well. From ‘Uweinat it was only 500 miles eastward to the Nile over a sand sheet of billiard-table smoothness. A strong mobile column could cover this distance in two easy days, seize the Aswan Dam, isolate the Sudan and hold Egypt to ransom. Bagnold knew that this situation would be readily apparent to at least one man on the Italian side.

The major’s mind turned to his Italian counterpart, Colonel Lorenzini, a man of vision, leadership and daring. Bagnold had met Lorenzini in the remote desert eight years previously and had been deeply impressed by his quality. Lorenzini would instantly grasp the situation in the same way as Bagnold, with all its potential for conquest. If the Italian high command had kept Lorenzini in Libya, surely they would be listening to him now. Complicating the situation and heightening its menace was the lack of aircraft for reconnaissance. The British had no machines available of sufficient range to fly south and investigate Italian intentions.

Summarizing the situation on paper, the analytical Bagnold outlined a suitable establishment for such patrols. He added a note suggesting that since no suitable army vehicles existed, it was high time to begin experimenting on a modest scale with half a dozen selected modern commercial vehicles. He made three copies of his proposal, and gave the original to Major General Percy Hobart to read. The hawk-faced “Hobo,” leading practical pioneer of modern armored warfare, who, as we have seen [in the Jan.-Feb. 1999 Journal], had risked his career in the cause of strategic mobility, was in no doubt as to the validity of Bagnold’s proposal: “I entirely agree,” said Hobo, “and I’ll send this on to Cairo. But I know what will happen. They will turn it down.”

Major-General Sir Bernard “Tiny” Freyberg, commander of the New Zealand Division in Egypt in 1940, was asked by Major Ralph Bagnold to provide personnel for his first Long Range Patrols. The mobility-minded commander agreed to lend some of his best men to assist Bagnold’s bold undertaking. Freyberg’s assent was repaid at the end of the North African war when he led his division in the famous “Left Hook” operation at Mareth that finished the Axis in North Mrica. This “Left Hook” went through country marked “impassable” on military maps because a New Zealand Long Range patrol had found a route.

Hobart was right. General Wavell had not yet come out of his attic. The Cairo brass lived in the peacetime routine of an internal security force stationed in Egypt since 1870 — an atmosphere lethal to any innovations such as Bagnold was now proposing. The formal Cairo view was that the desperate lack of defense troops and equipment made it essential not to provoke Italy in any way. Mussolini had a quarter of a million troops in Libya and a quarter of a million more in the south. He was still sitting on the fence. Roving patrols like Bagnold’s — even if they were feasible — might tip Mussolini into war. But this was only the formal view.

The real reason for the rejection of Bagnold’s proposal lay in the ignorance of the Cairo brass about the desert on whose edge their own HQ was located. Fear was the inevitable concomitant of this ignorance. One senior staff officer warned Bagnold that if he took troops into the desert where there were no roads “you’ll get lost.” On the officer’s wall hung a map of Egypt’s western frontier that was dated 1916. Detail in this faded out with the words, “limit of sand dunes unknown.” Comments on Bagnold’s suggestion of taking patrols across the 150-mile wide Sand Sea ranged from “ridiculous” to “madness.”

Physically a wiry man, without an ounce of spare flesh on him, Bagnold had the moral and mental fibre to match his physical resilience. He decided to try again. He showed the second copy of his patrol force proposal to General Hobart’s successor, after “Hobo” had been kicked out of the army to become a Home Guard corporal. The new armored division commander also approved of the plan and recommended it to Cairo. Again it was rejected. There were mutterings among offended brass-hats about this second attempt, and the “bloody nerve” of that major out at Matruh.

Shortly afterwards Bagnold went to Turkey in civilian clothes as the signals member of a small reconnaissance mission, sent at the invitation of that nervous and neutral government. When he returned to Cairo he found the scene transformed. Wavell had come out of his attic. He was now Commander-in-Chief Middle East, a military overlord with responsibility stretching from the Burmese border to West Africa, and from the Balkans to South Africa. A new headquarters, GHQ Middle East, was being set up in a different and cleaner part of Cairo, and an all-new staff consisting largely of officers fresh out from England was being assembled. The atmosphere was refreshingly alive.

Bagnold was appointed an aide to General Barker, the new Signal-Officer-in-Chief. Involved in the urgent improvisation of communications for Wavell’s gigantic and complex command, Bagnold forgot the desert until June 1940 brought crisis. France collapsed. Italy declared war. Both the Mediterranean and the Gulf of Suez were closed to shipping, virtually isolating the Middle East from a Britain itself set upon by a fleet of U-boats and the Luftwaffe. The threat Bagnold had foreseen with Italian entry into the war was now a stark reality.

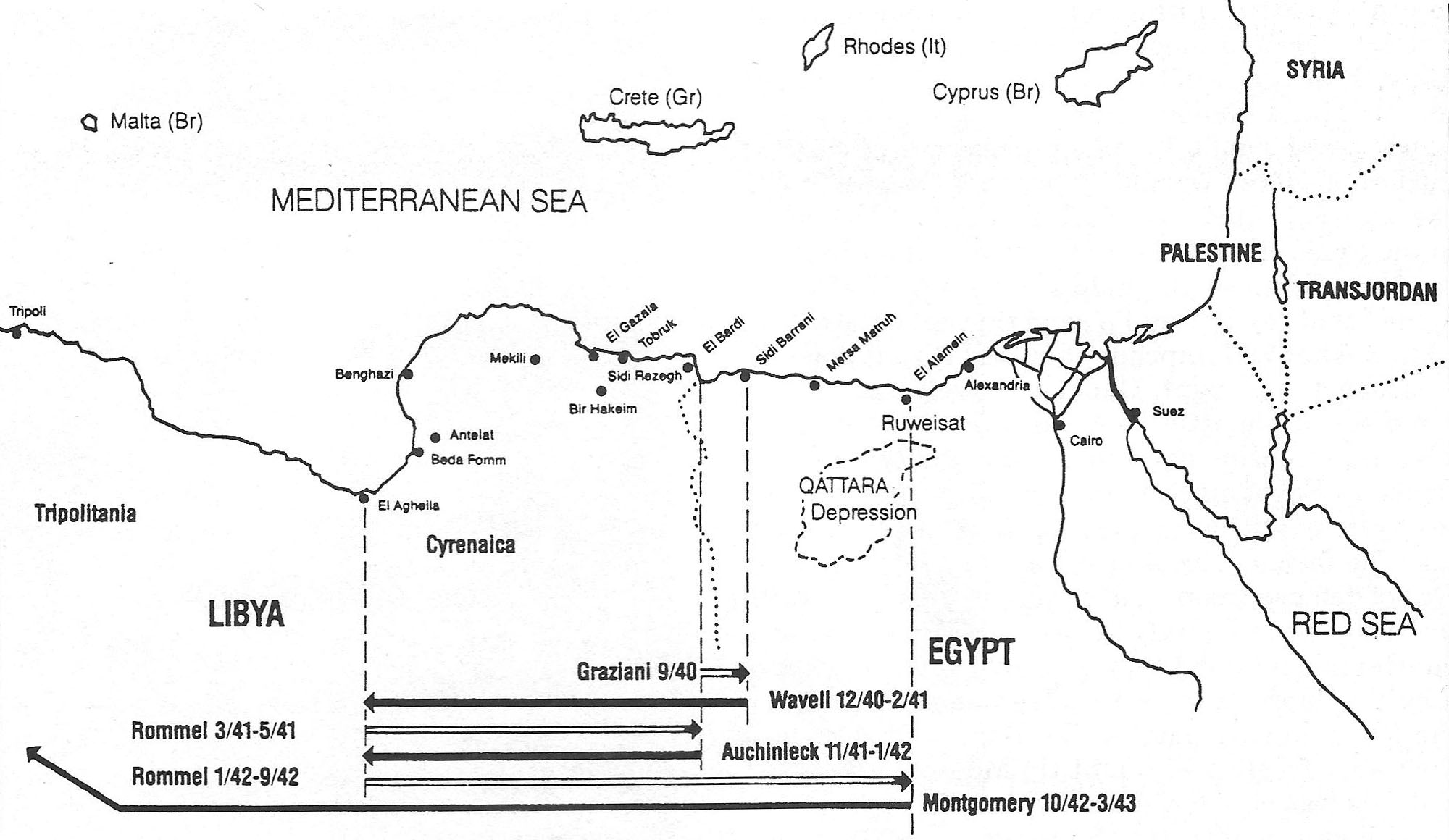

Marshal Graziani’s 15 divisions — a quarter of a million fighting men — would soon start rolling eastwards along the coast road towards Egypt and the Suez Canal. The Duke of Aosta’s similarly massive army in Ethiopia posed a similar threat, pincering in on the Sudan and Egypt from the south. Wavell’s immediately available defense forces were outnumbered ten to one. Reinforcements were coming, but with the Mediterranean closed, their arrival and deployment might be delayed for months. There were no war reserves of weapons or equipment. The situation seemed desperate.

The hour was late and Bagnold acted. He dug out the last copy of his earlier patrol force proposal and persuaded the head of the Operations Staff to place it personally on the commander-in-chief’s own table. Reaction was immediate. Within an hour, Bagnold was again alone with Wavell.

This time there was no oppressive attic office, lack of authority, or doubt about the crisis that was being confronted. The great man on whom so much now depended sat calm and relaxed in his chair, the one eye bright as before. His greeting set Bagnold at ease, for Wavell acted like a shy man welcoming a friend for a quiet chat. He indicated the rumpled paper lying on his desk. “Tell me about this, Bagnold. How would you get into Libya?” Bagnold walked over to a modern map of Western Egypt hanging on the wall, and his finger stabbed and then moved laterally. “Straight through the middle of the Sand Sea, sir. It’s the most unlikely place. The passage is here, due west of Ain Dalla. I’ve been along it, and I’m sure it will go all right, sir. And the going is good on the other side, what Clayton saw of it.”

The C.-in-C.’s weatherbeaten face was impassive. “What would you do on the other side?” he asked. “We would go far enough west to cross both the southerly routes to Kufra Oasis and ‘Uweinat. By reading the tracks, we could tell what recent traffic had been along them — the direction of travel and type of vehicle.”

Erwin Rommel, legendary commander of the German Afrika Korps, repeatedly scored victories against larger British forces. Of the Long Range Desert Group patrols, the “Desert Fox” once remarked: “They caused us more damage than any other enemy unit of comparable strength.”

Wavell’s expression remained unchanged. “What are the risks?” “Two, sir. First the weather. No Europeans have been into the sands in summer. If a south wind gets up, it’ll be pretty hot. How hot no one knows. Second, this map of yours, sir. You see the passage across the Sand Sea is printed on it, and it’s been on sale in Cairo for years.”

Wavell gave a comprehending nod. “You mean they might be waiting for you at Clayton’s cairn on the other side?” “Yes, sir. But it’s a bleak place for Italians to live at — no water, no life, no shelter and far from anywhere. It’s a reasonable risk to assume they won’t be there.” “What about your wheel tracks, Bagnold? They last for years.” “Over gravel country, yes sir, but its very difficult to follow wheel tracks from the air. The aircraft goes too fast. If you fly low enough to see the tracks, they suddenly jink sideways under the fuselage and are lost. Our tracks over the dunes, of course, would disappear with the first bit of wind.”

The C.-in-C. leaned forward a little in his chair, still inscrutable, but obviously interested. “And if you find there has been no activity along the southerly routes, what then Bagnold?” “How about some piracy on the high desert?”

Wavell’s face changed sharply. For an instant Bagnold feared he had gone too far. He had been too flippant with the C.-in-C. But the wrinkled face had creased now into a broad grin, the eye was very bright indeed and the whole head could have belonged to a pirate captain.

“Can you be ready in six weeks?”

“Yes sir.”

“Any questions?”

“Volunteers and equipment, sir.”

“Volunteers are a job for British Troops Egypt. I’ll see that General Wilson gives you every help. Equipment? Hmmm, yes. You’ll meet opposition.”

Wavell reached out and pressed a button. Expecting a clerk or orderly to enter, Bagnold was astonished when the bell was answered immediately by a lieutenant-general. He was Sir Arthur Smith, Wavell’s chief of staff. “Arthur,” said Wavell. “Bagnold seeks a talisman. Get this typed out for me to sign, now.” The C.-in-C. then dictated the most amazing order that Bagnold had heard in his military career: “Most Secret. To all Heads of Branches and Directorates. I wish any demand made personally by Major Bagnold to be met urgently and without question.”

Wavell turned now to Bagnold. “Not a word of this must get out. There are some sixty thousand enemy subjects of all classes loose in Egypt. Get a good cover story from my DMI [Director of Military Intelligence]. When you’re ready to start, write out your own operation orders and bring them direct to me.”

This was absolute carte blanche — regardless of desperate equipment shortages.

Leaving the C.-in-C.’s office still hardly believing his ears, Bagnold pondered the sudden reaction and quick decision at the suggestion of piracy. Why had that word precipitated action? He reviewed what he knew of Wavell in search of an answer. A brilliant, mobility-minded strategist, Wavell was a student of foreign armies and the mentality of their leaders. He was also a poet and author. A member of Allenby’s staff in the masterly Palestine campaign of the First World War, he was even now finishing a biography of the former chief. There was something else about Wavell — his grasp of strategic deception. He had made it a science. That must be it. The old man was planning an immense bluff to play for time!

The next six weeks were the most demanding and challenging of Bagnold’s life. A new and untried type of armed force had to be created from nothing, trained for operations never previously attempted and introduced to a hard and novel way of life — all in a few short weeks. Success would depend on combining Wavell’s talisman with a clear-cut plan and a knowledge of which button to push in the giant HQ machine. Bagnold threw all his energy into the task.

He would need the help of his prewar companions. Rupert Harding-Newman was the only one locally available in Cairo, serving as a liaison officer with the non-belligerent Egyptian Army. Guy Prendergast could not be brought from Britain. The archaeologist Bill Kennedy Shaw was curator of the Jerusalem Museum. Pat Clayton was on a surveying job in the wilds of Tanganyika. Shaw’s release by the Palestine government was arranged, and Clayton was located by the Tanganyika government and bundled aboard a special aircraft for Cairo. Shaw and Clayton were both in Cairo within three days of Bagnold’s request for their services, and both were put into uniform and commissioned as army captains immediately.

Bagnold and Harding-Newman meanwhile went shopping round the Cairo truck dealers. After trying out several types and makes, they settled on a one-and-a-half ton commercial Chevrolet with two-wheel drive. All the dealers in Egypt could supply only 14 of these vehicles. Harding-Newman persuaded the Egyptian Army to part with another 19. The Ordinance Directorate workshops put aside all other jobs to modify these commercial trucks to the specifications rapidly drawn up by Bagnold and Harding-Newman. Cabs were cut off, windshields were discarded, chassis and springs Strengthened and gun mountings installed. Open bodies were built to Bagnold’s design, into which modular ration and fuel cases fitted precisely for perfect stowage and prevention of fuel loss.

Patrol trucks of Bagnold’s LRDG like this one could cross desert dunes impassable to conventional units. This enabled them to carry out comprehensive surveillance of Axis supply lines hundreds of miles behind the front, and to harass the enemy’s rear and communications. Their intelligence-gathering activities and raiding operations immeasurably aided the Allied cause.

There were to be three patrols, each of two officers and 28 men, carried in ten unarmored trucks with a lighter vehicle for the patrol commander. Each patrol would carry a two-pounder gun, and each truck anti-tank rifles and machine guns mounted for all-round fire. Crews were to be individually armed with pistols and rifles. Bagnold specified endurance requirements unprecedented in military history. His tiny force was required to navigate and operate entirely on its own, far beyond reach of any help or supplies. Each patrol had to be self-contained for fuel, water, food, ammunition, spare parts and radio for 1,500 cross-country miles — the equivalent of 2,800 road miles — and for at least two weeks. Range could be increased by making double journeys to form supply dumps.

Every pound of weight mattered. Only absolute essentials could be carried. For this reason Bagnold had chosen the simpler two-wheel drive trucks. Gearing for the four-wheel drive vehicles added considerable weight and fuel consumption was higher. All the innovations introduced and proved by Bagnold for his expeditions years before were now brought into full use. Every vehicle was equipped with a pair of portable steel channels for “unsticking” from soft sand. These channels were placed under the rear wheels of a truck stuck in soft sand, and provided a sure method of extricating the heaviest vehicle.

Bagnold had also discovered how to conserve water. The regular radiator overflow was blocked up, and another hole made in the top of the radiator. From this hole, a hose was led to a vertical pipe reaching to the bottom of a two-gallon can bolted to the front fender. With the can initially half full of cold water, steam and boiling engine water which would otherwise escape were collected in the can. Half a minute after the engine was stopped, condensation caused all this water to be sucked automatically back into the radiator. As a precaution against long-continued boiling, possible when plowing through soft sand in a hot following wind, scalding water would ultimately spurt up from a vent in the can top on to the driver, forcing him to stop. With this ingenious Bagnold invention, trucks would need no extra water in hundreds of miles of hard desert driving. (By the end of the 20th century, virtually all passenger cars came fitted with versions of the device Bagnold invented in the 1920s.)

Navigation had long presented a problem in trackless, uncharted desert, mainly because a magnetic compass was unreliable in a moving car. In 1928 Bagnold had produced a simple, home-made sun compass by which the true bearing could be read accurately and quickly even when the vehicle was bumping over rough ground. The navigator could thus make a continuous record of bearing and mileage regardless of the course changes made by his leader to avoid obstacles. This record permitted a reliable plot to be made of the preceding route at every halt. The British Army had not adopted this type of sun compass, invented by one of its own engineer officers. The Egyptian Army had nevertheless seen the merits of Bagnold’s compass, and had fortuitously received a recent consignment from the London makers. Bagnold was able to borrow some of his own inventions from the Egyptians.

A Long Range Desert Group team at work “unsticking” a heavy patrol truck mired in soft sand. Ralph Bagnold, on his pioneering prewar desert expeditions, had developed techniques and simple equipment to free vehicles trapped in sand drifts. Such practical experience proved priceless in training his patrols to harass Axis forces over unprecedented distances in the North African desert.

Each patrol needed a theodolite, a surveying instrument used for accurate position-fixing by the stars at the end of each day’s run. The British Army could produce but one in the entire Middle East. A second was borrowed from Bagnold’s old friend George Murray, director of the Egyptian Desert Survey and Pat Clayton’s former chief. A third theodolite was located at Nairobi in Kenya and flown to Cairo.

Murray also helped by printing map sheets of Inner Libya on the same useful half-million scale as his own Egyptian maps. Although virtually blank, these sheets were essential for plotting courses and recording information along the route. The British Army had not yet devised any rational method for carrying the great number of maps it needed, toting them about in clumsy bundles of springy rolls which filled a three-ton truck. Bagnold’s prewar expeditions had conquered this problem, since maps had to be stowable in the confined space of a Model A or Model T car. Bagnold had devised light plywood portfolios in which maps were packed fiat. A supply of these portfolios solved the same problem now.

The health needs of the personnel demanded special consideration. Men would be exposed for long periods to desiccating heat by day while on a limited water ration, and to a large temperature drop after sunset in the desert. Prewar experience had demonstrated the adverse physical and psychological effects of a monotonous diet of army preserved rations under such conditions. Bagnold and his committee of old hands decided that a special ration scale was essential. Pat Clayton unearthed a nine-year-old copy of the Geographical Journal in which Bagnold had recorded a diet found suitable by his prewar expeditions. To the Supply Directorate, departure from the London-ordained ration scale was sacrilegious. There was resistance. With Wavell’s talisman and the full backing of the Director of Medical Services, Bagnold nevertheless got his way. The new patrol unit was allowed its special ration scale, including the daily issue of rum, abolished for the rest of the army since the First World War.

Staid British quartermasters raised their eyebrows time and again at Bagnold’s unorthodox demands. As the patrols would navigate by the stars over trackless desert, Air Almanacs were requisitioned. Army boots, which would fill with sand, were clearly unsuitable, so Bagnold had chaplis — sandals as worn by the Indian frontier tribesmen — made to special order. For protection against wind, sun and sand-blast, he chose the flowing traditional head-cloth of the Bedouin. Secrecy precluded buying this headwear in the Cairo stores, so a supply was arranged from the Palestine Police.

Each patrol needed a long-distance radio. Bagnold chose a lightweight No. 11 army field radio he knew to be reliable. Transmitting range of this set was officially 70 miles, but for a short period in each 24 hours it would have a much greater “skip” range- predictable according to a schedule varying with season and latitude. The No. 11. thus was less than ideal, but nothing else was available. When Bagnold’s patrols were equipped, the last No. 11 radio set in the Middle East war reserve went to his third patrol. When he drew his machine guns, three more remained as the reserve for the entire Middle East. Clearly Wavell was dependent on the success of this bluff.

Flank Attack on Murzuk. On January 11, 1941, eight days after General Wavell’s advancing forces had taken Bardia (800 miles to the northeast), two of Bagnold’s patrols attacked the Italian base and airfield at Murzuk, deep in southeastern Libya. Such actions on a remote southern flank, at a staggering distance from Cairo, unnerved the Italian commanders and caused them to doubt their own intelligence reports. By mid-February 1941, Wavell had trounced the greatly superior Italian forces, and occupied all of eastern Libya.

With his unique knowledge and enormous personal drive, Bagnold conquered each problem as it arose. His friend Bill Kennedy Shaw says of this period: “Bagnold’s secret weapon was that he knew the desert and he knew the army — and all the quirks of both.” The son of a colonel, his second home was the army and the desert his first love. This proved a winning combination, especially when the time came to turn from equipment to personnel. The imaginative major with unorthodox ideas knew enough about the army not to seek volunteers from among the regular troops. He was a realist. There was no time to unlearn such men of their routine ways. Resourceful, responsible men were needed, with the initiative that formal soldiering all too often extinguishes. His patrol personnel would have to absorb in weeks a mass of desert lore that Bagnold had acquired over two decades. They had to be fighting men, and yet skilled tradesmen, fitters, navigators and radio operators — as well as truck drivers and gunners. Keeping their small self-contained force operating for long periods in remote enemy territory would make heavy demands on their vital powers. They should be men accustomed to the outdoors.

General Sir Henry Maitland “Jumbo” Wilson, GOC [General Officer Commanding] of British Troops Egypt, suggested to Bagnold that he would find the men he wanted in the New Zealand Division. “The commander-in-chief has told me about this job of yours,” said Wilson. “Sheep farmers should suit you, I think. I’ll sound out General Freyberg. These people aren’t very keen on serving with ‘pommies,’ as they call us, but his division has arrived without its weapons, which were sunk at sea.” Wilson set up a meeting.

Armed with a detailed list of his requirements, Bagnold went to the New Zealand camp near Cairo. The bulky, battle-scarred “Tiny” Freyberg, with his unsurpassed fighting record in the First World War, was an almost-legendary hero to his own men, and he guarded their fortunes in turn with vigilance. His initial reaction was hostile. He was reluctant to lose his battalion commanders their best men, for this was in effect what Bagnold was asking. Fate, however, had made him the friend and confidant of Percy Hobart during the latter’s bitter struggle for strategic mobility. Hobart’s ideas had rubbed off on Freyberg, who was also mobility-minded, and Bagnold’s proposal was for mobility on a previously unimagined scale. Freyberg gave in. “All right,” he said, “You can have them, but only temporarily mind you.” As Bagnold left, Freyberg shot after him, “I shall expect them back.”

Freyberg’s circular to his division calling for “volunteers for an undisclosed but dangerous mission” produced more than a thousand applicants. Freyberg selected two officers from these, Captain Bruce Ballantine and Lieutenant Steele, and told them to pick their own team. When the little army arrived in Cairo, the modified trucks were just beginning to emerge from the workshops. The New Zealanders’ initial suspicion of English officers increased when they were received by a major and two captains who seemed to them to be somewhat elderly, greying gentlemen. Qualms were quickly supplanted by enthusiasm as they learned what they were to do, saw the equipment they were to do it with, and how everything had been thought out in meticulous detail.

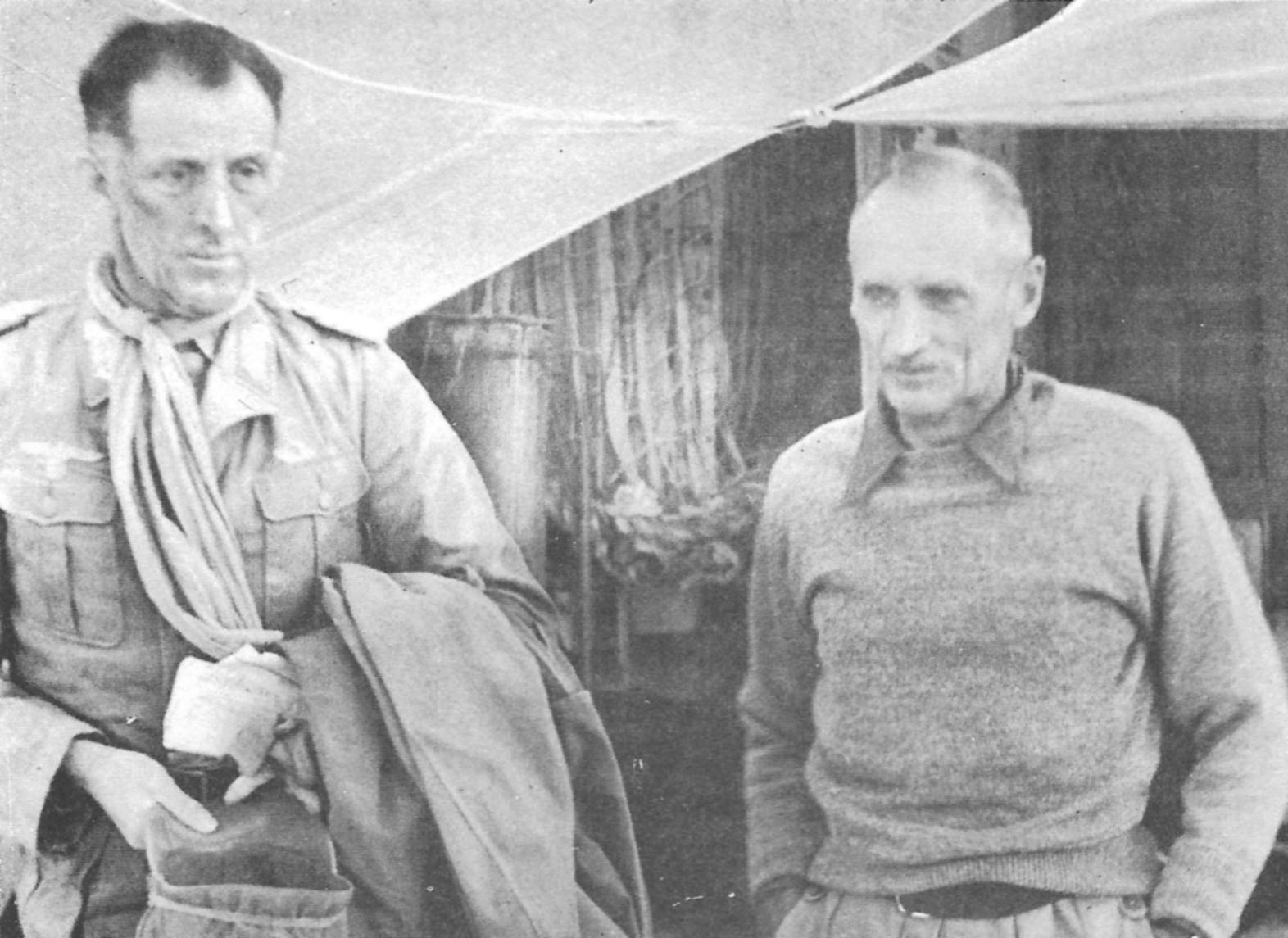

General Sir Archibald Wavell (right), Commander in Chief of British forces in the Middle East, talking with General “Dick” O’Connor, near Bardia, Libya, January 1941. Wavell’s later military setbacks against Rommel, April·June 1941, were not his fault, but Churchill lost confidence in him. Wavell was nevertheless later promoted to Field Marshal, appointed viceroy of India, and created a viscount and then an earl.

Under Bill Kennedy Shaw’s instruction, the six navigators-to-be quickly learned how to use the sun compass on the move, to plot dead-reckoning courses and to fix their nightly position by the stars. Unexpected help came from one of the volunteers, Private Dick Croucher, who admitted to being an ex-Merchant Navy officer with a first mate’s ticket. Like many other New Zealand soldiers he had concealed his qualifications for fear of having to spend the war on a busman’s holiday.

Within the six weeks’ time-limit set by Wavell, Major Bagnold was ready with three patrols. Dumps of supplies had been made at Ain Dalla near the Sand Sea crossing as part of their cross-country driving instruction. Another dump had been made at Siwa Oasis to the north of the Sand Sea, whence Pat Clayton had already reconnoitered a second route into inner Libya. With two trucks and five picked New Zealanders, he had penetrated southwards over the hundred-mile-wide north-western arm of the sands. Clayton also discovered and crossed another vast dune field, little realizing that twenty years later a rich oil field would be located beneath this barrier.

Wavell came personally to say goodbye to the patrols. The great general obviously loved adventurous enterprises, and his weathered face wore a subtle grin as he looked over his “mosquito columns” as he called them. “The old man looks as if he’s dying to come with us himself,” said a New Zealand trooper.

On September 5, 1940, the patrols slipped out of Cairo in secret. Lest the delicate sand structure of the passes over the dunes might not stand the disturbance of so many wheel tracks, two patrols commanded by Clayton and Steele drove to Siwa Oasis. They made a double journey south over Clayton’s new intra-dune route to make a dump on the enemy side at Clayton’s Cairn, the marker built by the surveyor ten years previously. The third patrol, commanded by Captain Mifford, with Bagnold, Intelligence Officer Bill Shaw and Adjutant Ballantine drove to Ain Dalla, to cross the Sand Sea directly from east to west. Graziani’s huge Italian army was already advancing along the coast road to invade Egypt. Siwa Oasis and its dump would probably fall into enemy hands shortly, closing the newer route to Inner Libya from the north. Everything therefore depended for future operations on the practicability of the Ain Dalla route, crossing the dune ranges at right angles. The burden of finally proving his conception thus rested squarely on Bagnold’s shoulders. If he failed, he would fail Wavell at a time when a bluff might be as effective as fifty thousand soldiers in the field — forces that Wavell did not now have.

General Wilhelm von Thoma, left, Rommel’s deputy, leaves the tent of Field Marshal Montgomery, right. Von Thoma was captured in early November 1942 during the Battle of El Alamein. During his meeting with Montgomery, he was shocked to find that the British knew more about the Axis supply situation than he did, thanks to “Ultra” code-breaking and detailed on-the-ground intelligence provided by Bagnold’s LRDG patrols.

The patrol quickly reached Ain Dalla, a deserted artesian spring on the eastern side of the sands, two hundred jolting miles from Cairo. The dump was intact. The absence of fresh camel tracks indicated that its existence was still a secret.

After a short rest, refueling and loading up from the dump, the patrol set out for the great dunes a few miles distant. Bagnold took the wheel in the leading truck. Months of planning and effort focused on this tough, austere Englishman whose insight, energies and vision had brought them all to this moment of challenge. He showed no emotion, but only the same pervasive practical confidence they had all come to respect. Tension mounted as the New Zealanders saw ahead a high rampart of sand stretching away unbroken to both horizons. Driving closer, they found the barrier rising ever higher above the fiat and rocky plain over which they were lurching. The dazzling yellow glare struck down from the rampart with ever-increasing intensity, blanching the eyes and so magnifying the steepness of the dune that it seemed like a vertical wall hundreds of feet high. Lumbering towards this frightening mountain in trucks carrying over two tons each, the challenge assumed a terrifying immediacy.

Halting the party some distance away, Bagnold let in the clutch and went rolling forward in his single truck to demonstrate the art of assaulting the dunes. Jamming his foot down to the floorboards he sent the heavy vehicle charging at the barrier with engine roaring and speedometer climbing. At 50 mph the wall of glaring yellow came rushing at them alarmingly. Clutching wildly at the dashboard, the man beside Bagnold let out a terrified bellow. “Christ,” he yelled, “you’re not going to …” Crashing head on at full tilt into the dune, all wheel motion suddenly seemed to cease. Nose tipping upwards, the truck rose bodily with its cargo as though hoisted from above. “It’s the first hundred feet that matters,” barked Bagnold above the engine noise. “If you can rush that without wavering you’re all right — if you know where to go.”

With a deft, shockless change of gear the truck continued to glide up a long but gentler slope to the crest, where Bagnold slowed and turned quickly. The men with him saw why. A 50-foot precipice of avalanching sand fell away beside them. Braking very gently, Bagnold brought the truck to rest. He’d done it. A ragged cheer went up from the trucks far below them on the plain.

Seconds later Bill Shaw drove his truck up with the same apparent ease. Alarm turned to confidence as the men saw that once again these veteran Englishmen knew what they were doing. Bagnold waved for the rest of them to tackle the climb. He had lectured them on the art of climbing dunes, but it could be learned only by doing it. Nerves of steel and a cast-iron gut were needed to charge that wall at full throttle. The drivers made the almost inevitable mistakes: lack of initial momentum, getting into the tracks of the truck ahead, wild gear-changing at the wrong moment, and trying to restart on the steep up-grade. A chaotic jumble of trucks resulted, their wheels stuck deep in bottomless sand.

Hours of back-breaking labor under the searing sun were needed to free the trucks, reassemble them and get them to the top. Bagnold was everywhere amid the sweating, cursing men, demonstrating, instructing, guiding — a leader by example. One by one the vehicles were extricated, in a gruelling ordeal that lasted all day. The sun was setting as the last truck reached the top.

They looked westwards over a new and fantastic world of endless repetitive curves. Solid ground could be seen nowhere, submerged as it was to an unknown depth. Range upon parallel range of giant dunes reached away limitlessly to the far horizon, two or three miles apart, like enormous ocean waves about to break but with their motion frozen. In black shadow the setting sun picked out the deep gulfs between each range of dunes. The Great Sand Sea. No more appropriate name was ever given to any natural feature.

Even Bagnold’s close friends of prewar years had felt and respected his deep natural reserve, feeling that nine-tenths of the man was essentially hidden. He withdrew by himself now, and sitting propped against a truck he added up the score in the greatest game he would ever play. Distance covered from Dalla: ten miles; distance to the other side: 140 miles of bottomless sand and 40 more of these monumental dune ranges. The trucks could do it, overloaded as they were. He and Bill Shaw had already proved that. The New Zealanders would soon learn. They were adaptable and remarkably intelligent. He comforted himself by remembering the mess his little party had made of their first attempt here ten years ago — and how they had suddenly got the hang of the new driving art.

Bagnold’s main anxiety was the weather. Right now it was good. Temperatures were little more than 100 degrees F in the shade, although things in the sun were too hot to touch. No sand moved in the gentle breeze, but if a “qibli” were to hit them in the Sand Sea, the results could be disastrous. He had once left a truck abandoned for two days, and found it lying on its side at the bottom of a ten-foot-deep scour hole. In a “qibli” the whole surface, now so still, would flow like water. They’d have to keep moving, yet it would be impossible to see through the mist of stinging sand grains, impossible to pick a firm route between dry quick-sands, or to keep men and trucks in sight. The Sand Sea could swallow the patrol under such conditions. Only Bill Shaw among them knew of the weather risk, and he would keep it to himself.

Bagnold began the next day with some short practical lessons. “Once you understand one of these dune ranges,” he said, “you understand them all. They’re all one family. Look at our tracks… barely half an inch deep. The sand here will take great weight, yet its quite loose. You can run your fingers through it. The reason it’s firm is that its surface is streamline to the wind. And the wind has fitted the grains one by one to make the densest possible packing.” He pointed to a nearby area. “See that different ripple pattern and the slight change of color? That sand was deposited at random, maybe centuries ago, by avalanching down a dune that has now marched on. Walk over and try it.”

Two soldiers walked to the area and sank in nearly to their knees. Once more, the grey-haired Englishman spoke the truth. “Many patches like that,” he said, “are covered over like thin ice over water. So keep your speed up, in the hope that your momentum will carry you through. But keep a sharp lookout for sudden precipices like this one. If you get stuck in soft sand, never, never try to get out without putting the channels under the back wheels. Remember that even this firm sand here is loose. Treat it like ice and be very gentle on both brake and clutch.”

This learn-as-you-go instruction paid immediate dividends. The patrol covered 40 miles of the Sand Sea the second day. Expertise quickly developed in unsticking bogged trucks, and in foreseeing where the surface was likely to be soft. Confidence increased with skill. On and on they ploughed, until by noon on the third day they emerged triumphant on to a vast, featureless plain of hard, sand-strewn gravel. They were across!

Looking back along their tracks, the men marvelled how anyone could find those narrow ascents on firm sand between so many avalanching sand cliffs. How could any man weave his way so unerringly across that bewildering landscape without a single landmark. How in hell had the major done it? Bagnold overheard some of their incredulous comments and wondered himself how he had been able to pull it off after a lapse of ten years.

Here on the Libyan side of the sands stood Clayton’s Cairn, the surveyor’s professionally-built pillar of loose stones. No man or animal had since visited the God-forsaken spot where they now stood. The only tracks were Clayton’s of ten years previously — still visible in the gravel. Bagnold’s underground route into Libya was still a secret from the enemy. While waiting for Clayton’s two patrols from the north to rendezvous, Bagnold mounted a return journey to Dalla for supplies. The men’s newly acquired skill showed in the scant seven hours they needed for the trip each way. When Clayton arrived, they had a substantial supply dump at Clayton’s Cairn, and the complete mosquito army stood ready for action. Bagnold’s bold concept had been vindicated in its most critical phase.

A military force could cross the Great Sand Sea, and in this brand-new fact lay considerable strategic possibilities. The inner desert no longer provided a defensive flank to an enemy attacking along the coast, but instead lay open before Bagnold’s little force. The slender north-south lines of communication from the Mediterranean coast to Graziani’s bases at Kufra and ‘Uweinat in the far south could be harassed at will.

On September 13, 1940, Graziani’s Libyan Army crossed the Egyptian frontier on its eastward advance towards Cairo and the Suez Canal. On that same day, Bagnold launched a two-pronged probe westwards into the heart of Libya. Mitford’s patrol struck westwards across five degrees of longitude, burning the stocks of petrol found on the chain of landing grounds along the Kufra air route. They examined the motor tracks leading south, and kidnapped a small motor convoy complete with vehicles, supplies and official letters.

Pat Clayton meanwhile struck south-westwards, passing between Kufra and ‘Uweinat mountain, right across southeast Libya to make contact with an astonished French outpost of Chad Province in French Equatorial Africa. Skirting the enemy garrison at ‘Uweinat, the patrols rendezvoused in the desert and returned via Ain Dalla to Cairo. The prisoners and captured letters were handed over to Intelligence, and proved to be a mine of information for General Wavell. From Clayton’s Cairn to Dalla, the patrols had travelled 1,300 miles completely self-contained. 150,000 truck miles had been covered without a single serious breakdown. This was only the beginning.

Other more aggressive raids quickly followed. Enemy desert outposts in the north were bombarded and destroyed, their garrisons routed or taken prisoner. Simultaneously the garrison at ‘Uweinat was attacked 500 miles to the south. A collection of aircraft was destroyed on the ground, and a large dump of bombs and ammunition blown up. The attackers seemed to emerge from the fourth dimension to strike and vanish like lethal ghosts. They appeared, struck and disappeared at widely separated points seemingly within hours of each other. British radio monitors in Cairo and elsewhere intercepted enemy messages of alarm and cries for help pouring into Graziani’s headquarters from all over eastern Libya.

All Graziani’s plans for the conquest of Egypt were based on the assumption, backed by his intelligence reports, that he faced only weak forces. Quick victory and occupation of the Nile Delta were anticipated within a few weeks. Yet within a few days of his first battalions crossing the Egyptian frontier he began getting these disturbing reports of attack — from a direction he believed to be completely secure. The British seemed to be everywhere, operating at incredible distances from their base. These assaults gave the war situation a new dimension. These far-ranging forces might attack his vital rearward lines of communication. Graziani ceased believing his intelligence reports and their central theme of British weakness. In overwhelming strength, the massive Italian army halted its advance. Wavell’s bluff was beginning to succeed.

Exploiting the situation to the full, Wavell ordered the number of patrols to be doubled. Twice as much piracy would spring from the additional patrols. From Long Range Patrols, the force was given a new designation, Long Range Desert Group (LRDG). The new distinguishing badge, showing a scarab riding a wheel, made its wearers among the most respected soldiers in the Middle East. Volunteers from the Brigade of Guards, Yeomanry regiments, the Rhodesian Army and the Indian Army joined the pioneer New Zealanders.

With the doubling of the patrols came a second carte blanche from Wavell: stir up trouble anywhere in Libya where the enemy can be harassed, attacked, shaken. Bagnold promptly obliged. He mounted an attack on Murzuk and its landing strip 1,100 miles as the crow flies from Cairo and 1,400 miles over the ground. Murzuk and back was far beyond the maximum range even of Bagnold’s patrols, but supply dumping by the Free French in Chad under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel d’Ornano, provided the necessary extension of range. (Colonel d’Ornano’s “price” for supply assistance was to be permitted to participate in the Murzuk raid. He was killed in action there.)

The brilliant Free French military commander Leclerc, stimulated by what he had heard of the capabilities of the British patrols, soon afterward resolved to capture the Italian stronghold at Kufra Oasis. Kufra was too tough a nut for Bagnold’s small force to tackle alone. By a miracle of improvisation, Leclerc overhauled and equipped sufficient local transport to carry a battalion of native Chad troops and two 75-millimeter field guns, together with supplies for the double journey of a thousand miles. The attack on Kufra, backed by Bagnold’s patrols, finally cleared the enemy from the whole interior of eastern Libya. The Murzuk and Kufra strikes were timed to coincide with Wavell’s counter offensive in the Western Desert. With the time Bagnold’s force had won, Wavell had built up his strength, and by February 5, 1941, he had smashed the Italian Army.

From this time until the end of the North African war, at least one patrol of the Long Range Desert Group was always behind enemy lines. The unit doubled in size yet again. An LRDG “private air force” was added, in the form of two WACO monoplanes purchased from an Egyptian pasha, which aided communication with HQ and evacuation of the wounded. The LRDG guided and carried commando units far behind the front to carry out daring raids. With its unrivalled travelling and navigating abilities, the LRDG could place espionage agents at the very gates of Axis-held strong-points almost anywhere in North Africa.

LRDG patrols themselves razed airfields in daring nocturnal raids, destroying hundreds of aircraft on the ground between 1940 and 1943. Beating up Axis supply convoys and mining roads hundreds of miles behind the front was their steady war routine. The LRDG set up “road watch” patrols, often lying within earshot of the enemy and reporting every vehicle, weapon and tank that passed by. This precise intelligence of Rommel’s supply position was one of Montgomery’s vital tools in the ultimate defeat of the Desert Fox. When Ritter von Thoma, Rommel’s deputy, was captured in the Battle of Alam Halfa just before El Alamein, the German general was shocked to learn that Monty knew more about the supply status of the Afrika Korps than he did. Most of this information reached Monty via LRDG road watch patrols.

The patrols continued to penetrate Axis territory pretty well as they chose. In the immensity of the desert their vehicles were rarely spotted. Bagnold’s original concept, his detailed development of it, and his far-seeing organization had transformed the inner desert from a text-book “defensive flank” into a serious liability to the enemy.

In action against the Axis forces in North Africa from first to last, the LRDG proved to be the most original, boldly conceived and brilliantly organized “private army” of the war. The success of Bagnold’s patrols helped break down official opposition to those commando-type formations, specialist units and “private armies” that fulfil novel and essential roles for which orthodox forces are neither trained nor equipped. The commando idea had been current for half a century or more, but its modern potentialities under special conditions had never been seriously considered. Those at the top seldom possess the special knowledge and experience to judge the probability of success. Luckily for the Allies, and perhaps for the world, Wavell was a commander willing to take risks. Without the stunning success Bagnold achieved, it is doubtful if some of the later private armies would have been authorized.

Unfortunately for Ralph Bagnold, the modernizer of this kind of auxiliary warfare, the modus operandi of his unique force had to be concealed in wartime from the enemy. Security blocked all details of its size and capabilities. Writing about the LRDG was initially forbidden and later heavily censored. For this reason, the LRDG was far less well-known in wartime than other auxiliary forces such as Carlson’s Raiders, Wingate’s Chindits, Stirling’s Parashots or even German Colonel Otto Skorzeny’s glider and parachute commandos. All these leaders became world famous.

Bagnold shared the anonymity of the LRDG in wartime. He left the unit in the summer of 1941 to become Inspector of Desert Troops,(note 1) and shortly afterwards deputy signal-officer-in-chief, with the rank of brigadier. He was decorated for his achievement in forming the LRDG with the Order of the British Empire — an exceedingly modest award for his unique contribution to the security of the Middle East and the defeat of the Axis. As he left the LRDG in 1941, his name ceased to be associated with it thereafter, except by those who knew the whole story and the true story. Later writers tended to assume that the colorful LRDG had come into existence as though grown on a bush. Bagnold’s personal indifference to publicity helped hide him to history, and he was already half-forgotten when his LRDG brought off the classic climax to its career.

From his vantage point on the staff, Bagnold saw the LRDG trigger the end of the North African war, just as it had opened the Allied account in 1940. At Mareth in Tunisia, where Rommel made his final stand, a “left hook” was smashed home against the German forces that ended Axis hopes in Africa forever. This devastating knock-out blow was delivered through country marked “impassable” on military maps. Leading the pulverizing stroke was Major-General Sir Bernard “Tiny” Freyberg, who had given Bagnold the first troops for his patrols — back when Bagnold was known in Cairo for his “wild ideas.” Freyberg had followed a route through “impassable” country found for him by, a patrol of the LRDG.

After the war, Brigadier Ralph Bagnold retired from the army for good, the green tranquillity of the Kentish countryside substituting for the golden wastes on which he found high adventure and fulfillment such as comes the way of few men. A busy and respected member of the British scientific community for decades, his fascination with the mysteries of natural physical processes was endless. He was a longtime consultant in the movement of sediments, beach formation and the like. In the words of Bill Kennedy Shaw: “Dry sand being difficult of access for him, he deals with wet mud.”

Although unknown in the United States outside professional circles, in 1969 Bagnold became the first recipient of the G.K. Warren Prize, awarded by the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. The prize recognized his contributions to fluvial geology. In 1970 he was awarded the Penrose Medal of the Geological Society of America. He was further honored by the Geological Society of London with its Wallaston Medal in 1971, and the International Association of Sedimentologists recognized his achievements with its Sorby Medal in 1978. Bagnold died in London on May 28, 1990.

Bagnold’s contribution to Allied victory remained but little known or understood even in his native England, which showered honors and historical affection on other desert and commando heroes. He could rightly be called the Allies’ hidden hero of the North African conflict. Without his “mosquito columns,” events in 1940-41 would have unfolded very differently. The mind boggles at the consequences of the seizure of the Suez canal in the autumn of 1940 by Graziani’s massive army. Rommel’s army was only a third as large when, two years later, the Desert Fox nearly took Egypt and the canal.

With the slenderest resources, Bagnold and Wavell — each a visionary in his own way — aborted the disaster of Egypt and the Middle East being lost in 1940. In modern military history there has rarely if ever been a bluff of such magnitude. Certainly there has never been one pulled with such elegance and finesse as Bagnold’s bluff, invested as it was with the conquering power of an idea whose time had come.

Note

1. Prewar companion and pilot Guy Prendergast relieved Bagnold as commanding officer (CO) of the LRDG, and happily flew half of the unit’s “air force,” which consisted of two WACO monoplanes. In the Bagnold tradition, Prendergast was the most mobile CO in the North African theater.

Author’s Note

“Bagnold’s Bluff” is a lightly edited version of a chapter of my book Hidden Heroes, published in 1971 by Arthur Barker, Ltd. (London). That was during the Vietnam war era when military men were widely disdained in America, and soldiers were sometimes even spat upon. The US market for military history was poor, and I went on to other things. Thus, Ralph Bagnold remained in the obscurity to which wartime security originally consigned him. The story of his remarkable strategic bluff in the fall of 1940 has therefore remained essentially unknown in the United States, and this essay is presented here to an American readership for the first time.

In August 1940, more than 200,000 Italian troops were massed on Libya’s frontier with Egypt, poised to seize Cairo and the Suez Canal and thereby threatening the loss of the entire Middle East to the Axis. The strategic and geopolitical consequences of such a loss would have been incalculable. Nothing better points up the appalling weakness of the British defenders at that time than the fact that when Bagnold drew weapons for his patrols from the available supply, he found just three Vickers machine guns remaining as the total reserve for the entire Middle East. General Wavell used more guile than guns when he sent Bagnold’s mosquito columns to raise hell on Graziani’s supposedly secure right flank. History has certainly credited Wavell fairly for his February 1941 defeat of the Italians, but it was Bagnold’s Bluff that caused wavering, apprehension and irresolution in the Italian command, despite the overwhelming numerical and material superiority of its forces.

The story of Ralph Bagnold strikingly points up how individuals can and do critically shape events of world importance, and thus make a real difference in history. This extraordinary man has never been given proper public credit for his enterprising role in keeping Egypt and the vital Suez Canal from Axis hands, and thus in altering the war’s entire course. During the war years, the story of Bagnold’s dune-crossing route to inner Libya had to remain secret. And while his patrol force was successively expanded, in 1941 Bagnold himself was promoted away to a lower-profile post, and thereby lost to history. While Wavell has received well-deserved acclaim for his victory over the Italians, Bagnold’s key role in Wavell’s strategic deception has remained veiled.

In writing this piece, I am grateful above all to Ralph Bagnold himself, with whom I had extensive correspondence. My long research on the Long Range Desert Group convinced me that the most fascinating of the many stories the unit generated was that of its creation, from absolute zero, in beleaguered 1940. As a retired Brigadier, Bagnold kindly assisted me with illuminating detail, which has appeared nowhere else, about this crucial start-up period. A gentleman of formidable intelligence, he kindly vetted my drafts of “Bagnold’s Bluff,” and provided valuable additions.

My good fortune, also as a young writer in the 1960s, was to become a corespondent of William Boyd Kennedy Shaw, former Major and LRDG Intelligence Officer. His book, Long Range Desert Group, published in 1945 by Collins (London), remains the basic work on the subject. An archaeologist and Arabic scholar, Shaw had been one of Bagnold’s dependable companions on the prewar expeditions into the Libyan Sand Sea, and beyond, which completed the primary exploration of that region. Through this ineffable gentleman, I was able to contact former Major Pat Clayton, another member of Bagnold’s prewar exploration group who later helped him organize the LRDG, as well as retired Captain Richard Lawson, former LRDG medical officer, who kindly loaned me his precious photo negatives of the period.

I am indebted to all these late gentleman for their generous and heart-warming aid.

From The Journal of Historical Review, March/April 1999 (Vol. 18, No. 2), page 6.

About the author:

Trevor J. Constable, born in New Zealand in 1925, has an international reputation as an aviation historian. With Colonel Raymond F. Toliver, he has authored a number of successful works on fighter aviation and ace fighter pilots. He has lived in the United States since 1952. He now makes him home in southern California.